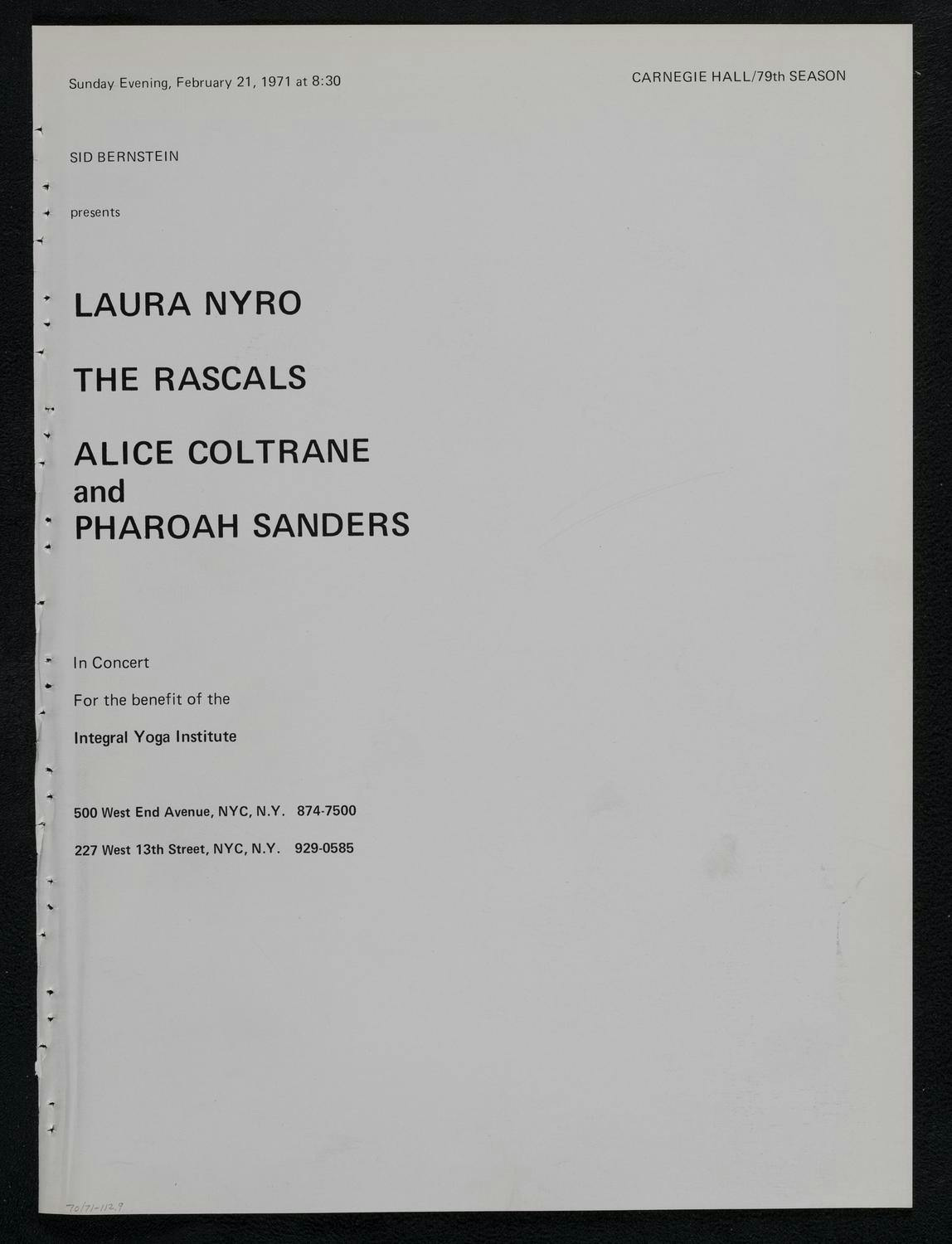

On February 3, 1971, a concert was held at Carnegie Hall, a benefit for Swami Satchidananda's Integral Yoga Institute. The bill included The Rascals, Laura Nyro, and Alice Coltrane. While that might seem an odd grouping of musical talent, there's a sense of cosmic fate to the way the stories of these musicians intertwined to arrive at Carnegie Hall on that winter's afternoon.

Of course, Satchidananda was the common element that linked these three musicians together. The yogi came to the United States courtesy of early benefactors Conrad Rooks and Peter Max. Through them he met many of the counterculture's elite members, and he stayed in New York for five months. In August 1969 he was helicoptered onto the stage at Woodstock to provide an opening address and lead some chanting. By 1970 he had established his Integral Yoga Institute in San Francisco.

Around the same time, David Geffen convinced Felix Cavaliere to produce Laura Nyro's fourth album, Christmas and the Beads of Sweat. Cavaliere was a singer, keyboard player, and songwriter with the band The Rascals, a group that played on the soulful, funky side of pop and psychedelic rock. Nyro was known to be difficult to work with in the studio, but Geffen felt they might get along well because she was an admirer of his music and because they shared a love for New York and Philadelphia soul, doo-wop, and r&b music.

The two did hit it off, and became close friends, though no romance ever developed, according to Cavaliere. It was Felix who introduced Nyro to Satchidananda, and she too became a follower, practicing meditation, though according to one acquaintance, "She couldn't follow the rules, but she liked the philosophy." According to Michele Kort's biography Soul Picnic: The Music and Passion of Laura Nyro: "Nyro also travelled to Sri Lanka with Richard Chiaro for a two-week yoga and meditation retreat with the Swami, a visit at which Cavaliere and jazz harpist/keyboardist Alice Coltrane--the widow of Nyro's jazz hero John Coltrane--were also in attendance." (pp.111)

John Coltrane had passed away from liver cancer in 1967, only two years into their marriage. As Alice mourned his death, she began to pursue recording her own music as well as continuing the spiritual journey she had begun with her husband. Together they had moved beyond the framework of their shared Christian upbringing to investigate Hinduism, Buddhism, and other systems of spiritual knowledge.

She recalled the start of her involvement with Satchidananda in an interview she gave in 2005 to Integral Yoga Magazine:

"In the early 1970s I was introduced to Gurudev (Swamiji at the time) by a friend who went to the Friday lectures in New York. I went to hear him and was highly impressed. For me to walk into the church and see so many young people gathered together was quite impressive. I would see Peter Max, Laura Nyro and others there. [Actress] Satya Kirkland put on a program on the life of Buddha and I had a chamber orchestra at the time so I played the music. Gurudev liked it very much and so my proximity to him developed from the programs and the music which was what I felt I could offer to Him."

In November of 1970, Coltrane had recorded the first four of five tracks that would appear on her next album, Journey In Satchidananda . Her record label, Impulse, was hoping the record would do well, and decided to record Alice's February 1971 Carnegie Hall performance in hopes of releasing a live record as a followup. But the record was never released, not coughed up from the vaults until a couple of weeks ago. That's unfortunate, because it clearly shows, even more directly than her studio recordings, that Alice Coltrane was a major musical force at the beginning of the '70s, and that her importance to avant-garde jazz, free improvisation, Black classical music, ambient, and devotional music has been routinely understated.

The musicians chosen for a double quartet-plus configuration are mostly familiar to those who follow John or Alice Coltane's music to any extent. Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp were both disciples of John Coltrane. Sanders played with Coltrane on his final set of albums as the saxophonist moved further into free jazz territory, and Shepp played on the Ascension album. Jimmy Garrison was the bassist from John's classic quartet, while Cecil McBee was a regular collaborator with Alice. Drummers were the hard bop turned avant-garde Clifford Jarvis, and Ornette Coleman collaborator Ed Blackwell. Alice plays harp and piano, and to this group is added tambura and harmonium.

The program begins with two tracks from the Journey in Satchidananda album, the title track and "Shiva-Loka." Both of these are relatively calm, drone-based pieces that fuse a modal base with deeply meditative improvisational solos. "Journey In Satchidananda" has a slightly different flavor than on its namesake album, where it opens with tamboura to establish a drone. Live, it opens with a gentle wash of cymbals and bass before settling into the groove from which Sanders' melodic statement will arise. It's easy to dismiss Coltrane's harp glissandi as mere washes of sound overlaid on the more straight-ahead jazz vibe, but they do more than that--they open the sonic and harmonic possibilities available to improvisers and they create an otherworldly flavor, as if they reveal something that is hidden. She also sets up a rhythmic, open backing to Sanders' flute and Shepp's soprano sax.

These performances created what was likely an expected vibe, one brewing with mindfulness and a meditative state--they were the offering laid at the feet of the Swami and the audience. But Coltrane was not done yet. Already over the suggested twenty minute time frame for her performance, she offers lengthy performances of two of her late husband's compositions.

"Africa" comes from Coltrane's 1961 record Africa/Brass, his first for Impulse. It is usually noted that it is the only album that augments Coltrane's quartet with a larger horn section, with arrangements by Eric Dolphy. But what is more important about the album is that it is a mission statement for the direction in which the saxophonist will head. He's not the free-blowing monster that emerged in 1965 on Ascension, but the roots of Crescent and A Love Supreme are there, and the brawny, raw tenor voice that he continued to develop in the '60s is in full bloom as well.

Alice Coltrane and her group approach the piece with the robustness that it calls for. Drums begin, crashing like waves against the shore. Alice begins to play blocky piano backing, not so different from the work of McCoy Tyner, but still establishing her independent voice. The two saxophonists blow back and forth on tenor, approaching the energy of John. After ten fiery minutes the piece really takes shape, with Jimmy Garrison, who played on the original Africa/Brass session, laying down a bass figure over which drums and piano cascade like rivers of lava. Those who doubted that Alice had absorbed a lot from her husband and now had further contributions to make to the music they had been creating together when he died were effectively repudiated this day at Carnegie Hall.

The version of "Africa" the group played that day clocked in at twenty-eight minutes. But they were still not finished, concluding with "Leo," a piece John recorded on a session of duets with drummer Rashied Ali, not released until 1974's Interstellar Space. Like much of John's later music, it is searching, roiling, and at times chaotic. In 2001 Ravi Shankar discussed talking to John about the sometimes painful aspect of his music:

"I had heard, just before meeting him, some cassettes of his latest compositions and I said, “John, if you don’t mind I will ask you a question. I just heard some recordings of your new compositions and I was very intrigued” …he looked perplexed. I continued, “ I was so impressed and found it amazing and touching as well,, but in places I felt you were crying out through your instrument and it was like a shriek of a tormented soul. I have heard the same from many other great jazz performers which is quite understandable because of their pain and the hurt of generations comes out in their music. But seeing and knowing you I thought that the interest and love of our tradition and music has helped you to overcome this…” I will never forget the expression on his face, and the words which he said with such a deep feeling which brought tears to my eyes. He said, “Ravi, that is exactly what I want to know and learn from you… how you find so much peace in your music and give it to your listeners.”

https://www.ravishankar.org/reflections/reminiscences-about-john-coltrane-2001

Spirituality implies a quest. It involves working with what is happening now no matter how much we don't want it. It's not about reaching a place of perfection and then riding it out. We will always feel pain, we will always have doubts or confusion. You get that sense from the group's performance of "Leo," and Alice creates a maelstrom on her solo, bringing the listener into a sonic whirlpool, right hand in constant motion against a thundering modal left hand.

Taken altogether, the performance given by Alice Coltrane and the group of musicians who took the stage that February afternoon was a major statement, one that solidified the direction taken by John Coltrane and showed that his work, his sound, his journey, could be expanded upon. It also showed that Alice Coltrane was a jazz artist of major importance. This recording is an important archival release that help re-situate Alice in the jazz firmament. It's easy to say that had it been released then it would have altered perceptions of her, but the fact is that she produced several important records between 1968 and 1971, yet the jazz world ignored or remained skeptical of her work until recently, when younger jazz musicians began to reveal her influence on their musical direction. We are fortunate to be able to hear this recording and partake of the experience, and to have the benefit of years to understand the importance of Alice Coltrane's music.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

Definitely in the running for reissue of the year - astonishing stuff!