Dexter Gordon: His Career on the Record

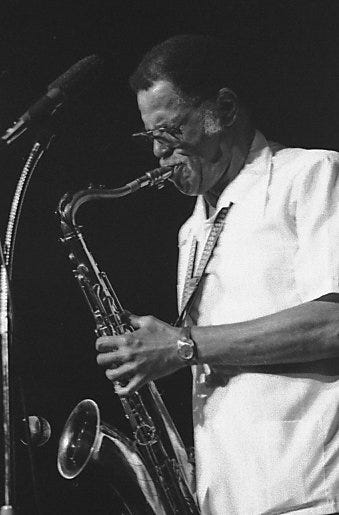

One of a handful of tenor players who defined tenor saxophone in the post-bop period, Dexter Gordon’s discography casts a long shadow over recorded jazz.

Dexter Gordon’s career spanned the period from the birth of bebop through the golden period of American jazz in the 1950s and 1960s, a period of European exile in the 1970s and a triumphant return to the States in ’76, leading to a period of renewed interest in his playing that lasted until his death in 1990.

Dexter Gordon first turned professional in December of 1940, when he was offered a job with Lionel Hampton’s band. He left Hampton in 1943 and spent six months in 1944 touring with Louis Armstrong. He then was a member of Billy Eckstine’s band until 1945, when he began to establish himself in New York as a regular on 52nd Street. There he played in a group with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, Curly Russell, and Max Roach. Gordon had a reputation for being smooth, even-tempered, and unflappable, as illustrated by the following story, recounted in Ira Gitler’s Masters of Bebop:

“One night at the Spotlight, a drunk dropped a handful of change into the bell of his horn during a solo. Outwardly impassive, Gordon continued his lovely ballad statement; when he finished, he calmly upended his saxophone and pocketed the coins…”

Gordon returned to L.A. (his birthplace) in the summer of 1946, carrying a boatload of experience and a heroin habit. He began to play in after-hours and weekly jam sessions, and soon encountered one of the West Coast’s leading tenor players, Wardell Gray. The two would trade choruses in after-hours sessions and eventually began recording together, with “The Chase” becoming one of their best-known sessions. “Wardell was a very good saxophonist who knew his instrument very well,” Gordon once said. “His playing was very fluid, very clean. Although his sound wasn’t overwhelming, he always managed to make everything very interesting, very musical. I always enjoyed playing with him. He had a lot of drive and a profusion of ideas. He was stimulating to me.”

Dexter Gordon and Gray recorded several sides in 1946/47. Dexter returned to NYC, working for a time with Benny Goodman, then back to L.A. in 1949, at which time Gray was himself working in New York. The two revived their duets sporadically from 1950 through 1952.

From 1953-54 Dexter Gordon was an inmate of Chino as a result of his heroin addiction. Gitler states that Gray was also addicted at this time. There are those who dispute this, but it does appear possible that Gray had fallen under the influence of narcotics. Gray still recorded occasionally and was playing with Benny Carter’s band in Las Vegas when he died under mysterious circumstances in 1955. Gordon had gotten out of Chino and went see Gray in L.A., only to discover that he had left for Vegas with Carter. Three days later he heard of Gray’s death.

In1955, Gordon recorded for the first time in three years. He recorded two LPs for the Bethlehem label, including one with Stan Levey and one under his own name, Daddy Plays the Horn. He also recorded a session for the Dootone label, released as Dexter Blows Hot and Cool. As Gitler says “all…(of these recordings)…demonstrate Gordon’s quicksilver swing, his audacity in the upper register, his tonal power and the apt use he makes of inflection whenever he contrasts a sustained note with those complex, mellowing phrases he manages with so expert a sense of time.”

Reissued as part of Shout! Factory’s Bethlehem Jazz reissues, Daddy Plays the Horn is indeed a wonderful Gordon session and one which shows him in the transition from his earlier, strictly bebop playing. As Gitler suggests, all of the elements that have made Gordon one of the most influential post-bop tenorists are in place here, albeit without the maturity that Gordon’s later Blue Note and Prestige recordings would show. Still, Gordon, along with the accompanying combo (Kenny Drew/piano, Leroy Vinnegar/bass, and Larry Marable/drums) sounds very comfortable, very relaxed here.

It was drummer Marable who nicknamed fellow L.A.-based tenor saxophonist Harold Land ‘The Fox,’ which became the title of his most-revered album, recorded in1959. This recording, as well as Land’s, demonstrate the quality of music that was being played on the West Coast in the mid-50s. This important bop and post-bop period is largely forgotten, in part because some of its best musicians were recorded infrequently. This was due to either a lack of name recognition, as in the case of Land, or personal difficulties, such as those Dexter Gordon was experiencing at this time.

In any case, Gordon is in excellent form on this date, and it is one well worth hearing for those who find that Dexter Gordon is their cup of tea. Kenny Drew, a disciple of Bud Powell (with whom Gordon also recorded) gives a great performance on this album and is the main diversion from Gordon’s own playing since Vinnegar and Marable are mainly employed as timekeepers and do little soloing. Gordon’s performance on the blues numbers, “Daddy Plays the Horn” and “Number Four” is ebullient and swinging. He tackles Bird’s “Confirmation,” and brings back echoes of his tenor battles with Wardell Gray, swinging in the Pres-influenced manner favored by Gray and Gordon in his young years. Drew again distinguishes himself with a blues and gospel-influenced solo that presages hard bop while still offering a Powell-esque edge.

On the ballads, “Darn that Dream” and “Autumn in New York,” Gordon is already demonstrating a very mature, melodic approach to ballads. In fact, it’s hard to believe that his ballad work acquired more and more depth throughout his career when one listens to “Autumn in New York.” A fast version of “You Can Depend on Me” rounds out the set with wonderful solos all round, and one feels very much like one has just heard a great set at a local club when the disc ends.

In 1960, Dexter Gordon became involved in the West Coast version of Jack Gelber’s play “The Connection”. Gordon composed music for the play, led the musical quartet that played onstage, and had a speaking role in the play itself. The East Coast version had featured music by pianist Freddie Redd, and the album, recently reissued by Blue Note as part of its Connoisseur Series, also features young alto saxophonist Jackie MacLean.

By the following year, Dexter Gordon had become one of a rapidly growing number of American expatriate jazz artists living and working in Europe. It is often made to sound as though Europe was a land of unlimited opportunity for jazz musicians at this time, a place where their race didn’t matter and jobs were plentiful. This idyllic picture is not quite accurate, however. The truth is that many of the musicians who went to Europe were not particularly well known, and there were those who had serious competition from the best European players, not to mention the protectionism of local musicians’ unions in European countries.

In addition, there were the old temptations of drug and drink, as musicians like Chet Baker and Richard Twardzik discovered during European tours in the 1950s. Gordon’s own bouts of depression and heroin abuse resurfaced during his European time, but he was apparently able to successfully combat them in the somewhat more supportive atmosphere of Copenhagen and Paris.

From 1961 to the middle of the decade, Gordon recorded seven albums worth of material for the Blue Note label: Doin’ Allright, Dexter Calling…, Go, A Swingin’ Affair, Our Man in Paris, One Flight Up, and Gettin’ Around. Most of these sessions were recorded in Paris, with Francis Wolff flying there to supervise the recordings. A few were done in New York during Dexter’s infrequent visits there. These Blue Note sessions are often regarded as Gordon’s very best work, and it’s difficult to argue with that assessment. Gordon was generally able to work with the best American and European musicians available at the time, and his playing is so very relaxed and swinging here that the word effortless seems insufficient to describe his ability to freely express his musical ideas.

Doin’ Alright features Gordon with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, pianist Horace Parlan, bassist George Tucker, and drummer Al Harewood. It features a number of outstanding Gordon performances on such tracks as the Gershwin brothers’ “I Was Doing All Right,” and such originals as “For Regulars Only” and “Society Red.” Gordon’s ability to play lengthy solos that were neither repetitive nor boring is starting to become apparent here, though nowhere near the lengths seen by 1963’s One Flight Up and also on his 1970s releases for the Prestige label. Dexter Calling was recorded during the same 1961 visit to New York.

In the summer of 1962, Dexter Gordon played a number of dates in New York City and utilized the rhythm section of Sonny Clark, Butch Warren, and Billy Higgins. The West Coast connection is very much in evidence, as both Clark and Higgins initially made their mark on the L.A. jazz scene. Warren hailed from D.C. before he migrated to New York City, and though he never recorded as a leader he worked with stellar musicians including Jackie McLean and Joe Henderson.

Gordon always considered Go! to be his best recording, and certainly his big, big tenor sound and perfusion of fresh ideas had to please him. In addition, there’s some of everything here: swinging near-bop (“Cheese Cake”, sensitive ballad readings “I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry” and “Where Are You”, a bossa-infused “Love for Sale” and a hard-driving “Three O’Clock In the Morning.” Only two days later Gordon recorded A Swingin’Affair with the same rhythm section. Of particular note on that album is a hot version of “Soy Califa.”

Our Man In Paris was to have included Kenny Drew and other musicians playing some original Gordon compositions. But when Bud Powell replaced Drew at the piano, the decision was made to record a series of standards. With original bebop drummer Kenny “Klook” Clarke on drums and Frenchman Pierre Michelot on bass, Our Man in Paris becomes an essential recording in a career of essential recordings. From the opening “Scrapple from the Apple,” the finest recording of this classic since Bird passed away, it becomes apparent that this session will be one for the ages.

Bud Powell, while far from the sound and fury of his best years, plays very lucidly and his solos, while brief, have a real sense of logic about them that belies the idea that he was completely spent by this time. Indeed, a number of sessions recorded by Powell in Europe around this time confirm that, when surrounded by stimulating musicians or environment, Powell was still capable of performing very well. Other standout performances here include Gordon’s very vital reading of “Willow Weep for Me” and a fairly incendiary version of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Night in Tunisia.”

The following year saw the recording and release of One Flight Up. This time Gordon is in the company of trumpeter Donald Byrd, pianist Kenny Drew, drummer Art Taylor, and Danish bassist Neils-Henning Orsted Pedersen, a new find at the time. The album was to have had four tracks, but Wolff determined that the recorded performances of the Gordon original “King Neptune” were not up to par, so it was not included. No matter—the eighteen-plus minute version of Byrd’s composition “Tanya” took up a whole side and lengthy blowing sessions on Drew’s “Coppin’ The Haven” and the standard “Darn That Dream” offered enough to fill out an album. The Rudy Van Gelder Edition of this recording restores the better take of“Neptune’s Dream.”

What might have been a lackluster blowing session for lesser artists is a real winner for Gordon. His playing has a new energy and edge here, especially on “Tanya,” a piece that would become a mainstay of Gordon’s live repertoire for some time to come. When Pedersen kicks into a walking rhythm on the song’s bridge with Taylor offering blasts of counter-rhythm, it feels about as good as jazz gets. Byrd is also playing well on this session, and he certainly is another artist whose Blue Note work is considered to be among his very best.

1965’s Getting’ Around is considered to be something of a second-tier recording among Gordon’s Blue Note work, but considering the level set by Gordon on these earlier recordings, that hardly makes it bad. The rhythm section is from Lee Morgan’s Sidewinder recording (Barry Harris, Billy Higgins, Bob Cranshaw) along with vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. The results are smooth and sophisticated—listen to Gordon’s work on “Shiny Stockings.”

During the entire time he recorded for Blue Note, Gordon stayed in touch with Prestige Records producer Don Schlitten. In 1969 he signed a two-record deal with Prestige and recorded sessions for The Tower of Power and More Power. Prior to signing with Prestige, Gordon had recorded some sessions for European labels such as Steeplechase and Black Lion. Tower of Power and More Power feature Barry Harris, Buster Williams, Albert “Tootie” Heath, and on several tracks, guest tenor player James Moody. The playing here is congenial, relaxed, with no attempts being made to break new ground. No, this is the sound of a master musician doing the very thing that he is famous for, the thing that he does.

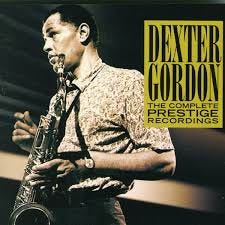

The 70s Prestige albums have never carried the cachet of the Blue Note sides, but one reason for that may be that several of the Prestige albums became unavailable for a time, perhaps leading some to surmise that the sessions were less than essential. In 2005 Prestige remedied this situation by releasing the mammoth 11-CD box set Dexter Gordon: The Complete Prestige Recordings. This set documents all of Dex’s work for Prestige from 1969 through 1973, with some earlier work for the label (a recording with Wardell Gray, the 1960 album The Resurgence of Dexter Gordon and two performances from Booker Ervin’s Setting the Pace featuring pianist Jaki Byard and bassist Reggie Workman) thrown in for completeness. Hearing Dexter tear into “Montmartre” and “Lady Bird,” along with equally interesting alternate takes of each makes it immediately clear that this is a body of work that is in no way inferior within the artist’s discography.

Before returning to Europe, Gordon played live gigs at Baltimore’s Left Bank Jazz Society on May 4, 1969. These were recorded and subsequently released as the albums L.T.D. Live at the Left Bank and XXL Live at the Left Bank. Gordon, along with rhythm section Bobby Timmons, Victor Gaskin, and Percy Brice, burns through a series of tunes, including Monk’s “Rhythm-A-Ning” on which he plays a seven-minute solo that remains vital, energetic, and bristling with inventiveness throughout. There’s a beautiful reading of “Misty” on which Gordon doesn’t really deviate from the melody all that much but on which he nonetheless puts his distinctive stamp. A lengthy “Love for Sale” again hints at the bossa rhythms of the version on Go!, but which gets a bit more down-home feel from Timmons. Dexter Gordon with Junior Mance Live at Montreux is represented by standouts such as a lively version of “Fried Bananas” and a sumptuous reading of Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady.”

On 1970’s The Panther, Gordon is joined by pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Larry Ridley, and drummer Alan Dawson. Opening with an authoritative version of Clifford Brown’s “Blues Walk,” the group immediately establishes itself as top-notch. This is an album that can truly be set right beside Gordon’s best Blue Note recordings. Gordon was paired with Albert Ammons for a retake on “The Chase”, and Gordon’s last real two-tenor collaboration. During the same stateside visit, Gordon also recorded the sessions for The Jumpin’ Blues, an album that featured ever-tasteful pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Sam Jones, and drummer Roy Brooks. Gordon lays down a definitive “Rhythm-A-Ning,” which he was playing often. There’s also a wonderful performance of “Star Eyes” utilizing the Parker original’s rumba opening. When Gordon soars as the rhythm section breaks into a straight-ahead swing, it feels like freedom itself.

In1972, Gordon returned to the States to record sessions for two additional Prestige albums. However, the sessions went so well that almost all of the material was released over the course of three albums: Tangerine, Generation, and Ca’Purange. Generation (and one single track on Tangerine) features Freddie Hubbard, Cedar Walton, Buster Williams, and Billy Higgins. This is a distinctive group, and again the results of this recording largely rival anything from the Blue Note Years. Most of Tangerine and all of Ca’Purange feature something of an Afro-funk soul feel. These sessions feature Thad Jones on trumpet and flugelhorn, Hank Jones at the piano, Stanley Clarke on bass, and Louis Hayes on drums. Without the use of electronics, these performances brought Gordon’s hearty post-bop tenor sound firmly into the modern jazz mainstream without sacrificing or dumbing down his artistry at all. Gordon handles “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” as though it were a standard from the Great American Songbook, and he tears up Sonny Rollins’“Airegin” like no one this side of Sonny could. Again, Gordon is at the top of his form, and the sheer volume of his stellar recorded work comes prominently into focus.

The last disc in the Prestige set includes Dexter’s 1973 live at Montreux album Blues a la Suisse. Featured are pianist Hampton Hawes, who works both acoustic and electric piano, bassist Bob Cranshaw, and drummer Kenny Clarke. Some may bristle at hearing Dexter with electric piano, but it’s a needless worry: Gordon’s musical spirit is too strong to be waylaid by something as innocuous as an electric keyboard, particularly when it’s played as funkily and tastily as Hawes does here. For the final track, the group is joined by guests Gene Ammons, Cannonball Adderley, Nat Adderley, and Kenneth Nash for “Treux Blue.” Overall, the majority of the music contained on the Complete Prestige Recordings is very high quality, and will certainly not disappoint Dexter fans in any way.

At the end of 1976, Gordon returned from some 14 years in Europe to play some dates at the Village Vanguard. Unexpectedly, Gordon was the jazz world’s darling, with critics lauding his mature playing and a new generation of listeners coming to hear him. Gordon returned to the states and enjoyed a renewed career until his death in 1990. Less than a year after his triumphant return, Gordon recorded Sophisticated Giant for Columbia. In 1978, Gordon went back into the studio with a band comprised of pianist George Cables, bassist Rufus Reid, and drummer Eddie Gladden and emerged with the classic album Manhattan Symphonie, which remains a highlight of his discography.

Manhattan Symphonie is another perfect Dexter Gordon album, and the fact that it was on a major American music label didn’t change Dex’s approach one bit. He and the band are playing absolutely top-notch bebop-influenced jazz, and it’s hard to believe this kind of thing was getting recorded and released at the time. The group revisits the signature tune “Tanya,” with Cables offering an incredibly church-tinged flourish to the piano vamp, and Dexter sounding like his tone has been mellowed in an oak barrel for a couple of decades. Comparing the Gordon of Manhattan Symphonie with Daddy Plays the Horn, or even his very earliest Blue Notes, one hears what was missing from Dexter’s sound then—experience and the distillation of one’s voice down to its absolute essentials, devoid of extraneous trappings.

Dexter went on to greater fame in the States in the mid-1980s when he contributed to the soundtrack of the film Round Midnight, as well as taking a starring role in the film. A couple of recordings of soundtrack music from the film were released, and Gordon also did some work with Herbie Hancock, another contributor to Round Midnight’s soundtrack.

Gordon passed away April 26, 1990, leaving behind a recorded legacy rivaled by few modern jazz musicians. Gordon’s work, at all stages of his career, is something to be savored like the finest of spirits. Rest assured that anytime you pull out a Dexter Gordon recording, you will be hearing a musician of the highest order whose recorded output is remarkably consistent and appealing.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

GO! was my first - and still my favorite - jazz LP. I need to listen to them all.

Thank you!

I played the Jazz At Lincoln Center ceremony that inducted Lennie Tristano and Dexter Gordon into their hall of the fame - I was part of Lennie Tristano tribute. It was a beautiful event, July 2015.