In 1974, Frank Sinatra was 59, and unhappy in the way that only a white, wealthy, world famous man can be. He didn't like the way that the world was changing, with increasing recognition for black Americans and women, and long haired freaks running in the streets and creating mayhem. Having heavily supported JFK in '64 and campaigning for Humphrey in '68, Frank was now deeply Republican, supporting Nixon during his re-election run in '72 and developing a close relationship with Nixon's unpopular Vice President Spiro Agnew.

His general unhappiness, rising from a growing sense of powerlessness, had likely been stoked by the boundaries of his very public retirement in 1971. At the age of 55, after 36 years in show business, Sinatra retired with a farewell concert at Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, leaving the stage with his rendition of "Angel Eyes." For the next two years the singer tried to adapt to a schedule of golf and early dinners while his peers, including Bing Crosby and Sammy Davis, Jr. insisted that he'd be back after a brief rest.

He had been goaded into retirement by a number of things. Record sales were low, partially because Sinatra's ageing audience bought fewer records and younger listeners had no interest in his renditions of saloon songs and great American musical theater numbers. Reviews were less than stellar, with many critics and writers saying that Frank was no longer in possession of a magical vocal instrument, though most had to admit that he was able to compensate with his innate sense of phrasing and swing as well as his trademark bravado.

Following his last unquestionably successful album, My Way in 1969, Sinatra and his handlers had tried a number of gambits to restore his music career to its former glory. He recorded an album of songs by Rod McKuen, and a song cycle, Watertown, an attempt at a pop concept album that isn't bad at all. He went back to working with Jobim for half an album. None of these things worked, and so Frank was increasingly left to sing contemporary pop songs that lacked the harmonic and, frequently, lyrical complexity of his usual classic material. Because of his sense of timing and sometimes because of the arrangements that were written to back him up, his performance level, both on record and live, could still be quite stunning.

When the least believable retirement since Ziggy Stardust came to an end, Sinatra re-entered the fray with Ol' Blue Eyes Is Back. On this album he performs songs by 'newer' Broadway and Tin Pan Alley songwriters like Joe Raposo, Stephen Sondheim, and Paul Anka. Back in the saddle as producer was Don Costa, who also provided many of the musical arrangements. This was a return to the Reprise sound that Sinatra and Costa had created with the Cycles and My Way albums. Newer pop songs were carefully chosen and sprinkled amongst standards or cabaret material/show tunes to create albums that, while perhaps not the equal of his mid-sixties Capitol output, maintained the sense that he was creating albums of songs with which he was emotionally involved.

His 1974 album, Some Nice Things I've Missed is similar, but all of the songs come from the period 1971-73, the period of Sinatra's 'retirement'. Frank turns in solid performances of songs like Michel Legrand's "The Summer Knows" and "What Are You Doing The Rest of Your Life?" and, surprisingly, David Gates' "If." Even if he waxes gravelly and the higher notes quaver a bit, it merely serves to show that his musical instincts are still right on point.

But there are some low points that really hit hard, like the swingtime arrangements of pop music numbers "Sweet Caroline," "Tie A Yellow Ribbon 'Round the Ol' Oak Tree," and "Bad Bad Leroy Brown." These performances launched Joe Piscopo and a bunch of other less than flattering Sinatra impersonations that stuck around for the rest of the singer's career. Not only did Sinatra not seem emotionally involved with this material, he didn't really seem to care about it at all.

Which may have been the case, because Sinatra was going back on stage, performing in front of audiences again, and there he gave newer material very short shrift. That continued from '74 straight through the rest of his career: as he made fewer records, his live performances could mine a repertoire that spanned four decades, and there were only a few slots given to the occasional performance of "If" or George Harrison's "Something," or a handful of other rock era tunes that were deemed worthy by Sinatra and his audience.

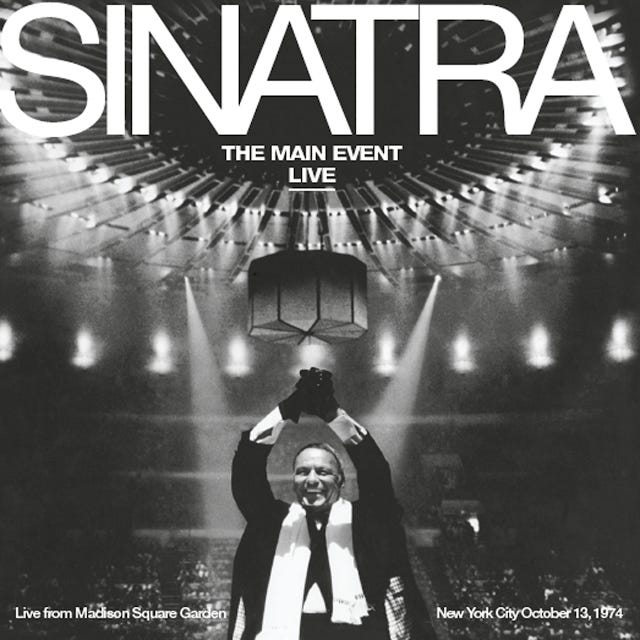

Sinatra launched a ten city comeback tour, his first concert tour in six years, with performances benefiting Variety Clubs International. Performances sold out weeks in advance, and fans packed the stadiums where he performed. With stops at venues like Philadelphia's Spectrum and New York's Madison Square Garden, the show was presented on a level with large rock concert tours of the time. The tour would climax with a series of shows at the Garden, and a one hour television simulcast of one of the MSG shows on October 13.

Titled The Main Event, the shows were presented on a stage surrounded by a fake boxing ring. The Madison Square Garden simulcast show opened with an Overture featuring themes from various Sinatra songs, and an introduction by sportscaster Howard Cosell. Like all Cosell, transcription doesn't really do it justice--you have to hear the words in the cadence of his voice: "Madison Square Garden...jam packed with twenty thousand people plus...just people. People from all walks of life. People who are young, and people who are old, here to see, hear, pay homage...to a man who has graced four generations and somehow never found a gap. Hello again, I am Howard Cosell. And I've been here so many times, and in a curious way, this event, live with the king of entertainment, carries with it the breathless excitement and anticipation of a heavyweight championship fight."

Cosell goes on to point out a few celebrities in the crowd, including Rex Harrison ("Professor Higgins if you will"), Carol Channing ("Hello, Dolly!"), Walter Cronkite, and Robert Redford, before introducing Sinatra himself--'who knows what losing means, as so many have. Who made the great comeback...Ladies and Gentlemen, Frank Sinatra!"

Frank wastes no time, stepping into the ring, knowing he is backed by first rate charts played by Woody Herman's tight Young Thundering Herd, though Woody isn't there himself tonight, with the group being led by Sinatra's longtime pianist Bill Miller. His opening number, as it has been throughout this tour, is "The Lady Is a Tramp," played at an optimal tempo to emphasize its heavily swinging nature. The song is familiar to most audiences, and Sinatra uses it as a workshop in how to win over the crowd immediately with timing, charm, and a sense of humor. But there is never any question that Sinatra has this song by the throat and he is driving it home.

His by this time familiar practice of dropping words, or adding words, or changing lyrics completely is on full display here. He gives the song a full airing with relatively little embellishment, and when he sings of how she loves the 'free, fresh wind in her hair' the listener can't help but notice how much space there is between those words.

After a brief instrumental interlude, he goes through the lyric again, but this time he has his way with it, not only in terms of lyric but also musically, stretching the melodic width of the phrase 'she adores the theater.' When he hits that bridge this time he's got some extra: 'she loves the free, fresh, crazy, knocked-out, koo-koo wind in her hair' he tells the MSG audience, and it is clear the Chairman has called this meeting to order. Sinatra wins round one by a mile.

It is instructive to listen to Sinatra's performance at The Spectrum from October 7, released in full as part of the live Standing Room Only release from 2018. Here we get to hear the show without the trappings of a televised event. We hear the evocative Overture that includes themes from "All the Way," "It Was a Very Good Year," and "My Kind of Town" without the Cosell intro. While Sinatra follows the same performance method on "The Lady Is a Tramp" he isn't quite as loose with pure adrenaline, saving the final 'koo-koo' lyric for his New York crowd. Yet the Philly audience is extremely welcoming and enthusiastic, even managing to move Frank to making a personal remark. He seemed surprised by the level of affection that he generated amongst the Philadelphia audience.

Reprise Records also recorded the shows with the goal of releasing an LP that would sell strongly to his hard core audience as well as to more casual fans and people who would buy it as part of the cultural moment. The resulting album, a separate project from the television special, was a constructed performance--not all of the performances came from the October 13 show at MSG, and a couple of songs are cut together from different performances to make a single track. This is another technique of the rock and roll era, and it's difficult to find a live rock album from the seventies and eighties that hasn't been cut together in the studio.

The selections create an incredible performance, with the inclusion of "Bad Bad Leroy Brown" being the only misstep. Otherwise, you get classic Sinatra performances of classic Sinatra repertoire: "I Get a Kick Out of You," "Autumn In New York," "I've Got You Under My Skin," "Angel Eyes," "My Kind of Town," and the finale, "My Way."

So, was The Main Event a success? In terms of redefining Frank Sinatra as he entered the late stages of his career, it was. The message was clear: from here on Sinatra would rest his reputation on live performances of standard material from across his career. No more pandering to the rock and roll era. He only recorded two more studio records after that, not counting the absolute debacle of 1993's Duets. So yeah, he made the comeback stick with The Main Event.

The New York Times' John Rockwell wrote positive reviews of both one of the Madison Square Garden concerts and the concert that was televised:

"Both nights. Mr. Sinatra managed to hold his audience securely under his spell. The voice may have its failings—it always did, really. But it has its unique virtues, too, and as a stylist of a certain kind of pop‐jazz sensibility, Mr. Sinatra remains the master of his generation.

There were many of that generation at the Garden over the weekend, but Mr. Sinatra's appeal is more to a social strata—the white middle class and lower‐middle class—than to a particular age group. For them, he remains a spokesman and even a hero, and all his much publicized private imbroglios and feuding with the press only add leaves to his laurel."

But in terms of overall cultural impact, the response wasn't all he could have hoped. According to Kitty Kelley's biography His Way:

The audience screamed its approval, but the ratings were abominable. Frank's show, ballyhooed as 'a once in a lifetime event 'live' at Madison Square Garden,' fell to number forty in the week's ratings, an indication that most of the country preferred watching Kojack and reruns of Father Knows Best. Even the critics were disparaging, especially Rex Reed, who said that Frank was sloppier than Porky Pig, with manners more appalling than a subway sandhog. (P. 427).

Frank's issues with the press go back a long way into his career. One problem is that, in the seventies, he was still being evaluated and criticized by the descendants of the tradition of the Hollywood reporter. Originally gossip columnists such as Hedda Hopper and Walter Winchell, they were the forerunners of today's entertainment press, including People and the like. Reed was known largely as a film critic, but of course he held forth on personalities from other performing arts that were big enough to draw his attention.

Another member of the press that Frank was especially irate about was Rona Barrett. The insults and invective he leveled at her were sickeningly misogynistic. In fact,, he despised female reporters even more than the homosexual Reed. He caused Australia's many labor unions to fly into an uproar when he insulted an Australian female reporter who had written about him. He had become like the mafioso he was so famously associated with throughout his career: coarser and more viscous.

The Main Event is a good record, and that's what matters when you put it on. It's a document of a certain time and place and of the career of the man in the ring, gloved hands clasped over his head in victory. It's the last Sinatra record I paid any attention to as his career glacially moved along for twenty more years until his final live performance at the Frank Sinatra golf tournament in February of 1995. This time his retirement lasted three years until his body, hectored by a bad heart, dementia, and bladder cancer, took him out for good.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

Great piece, Marshall! I don't think I've ever listened to the album, and you've got me curious...although I might skip Leroy Brown. I'm also storing away Rockwell's "adding leaves to his laurels" line to steal later, LOL.

I was at "The Main Event" at the Garden. I had near front row aisle seats, too. (I was still in the music business). Steeped in rock as I was, I was still amazed at his charisma. I understood what people meant by "phrasing" to compensate for whatever loss of efficacy in his pipes. I saw him and reviewed him about 10 times over the next 20 years once I became a newspaper critic a year later: Saw some great nights, and some bad ones, until I wrote a column begging him to retire that went "viral" thanks to syndication. Frank was often unhappy: The word we use now was not diagnostic then: He suffered from depression.