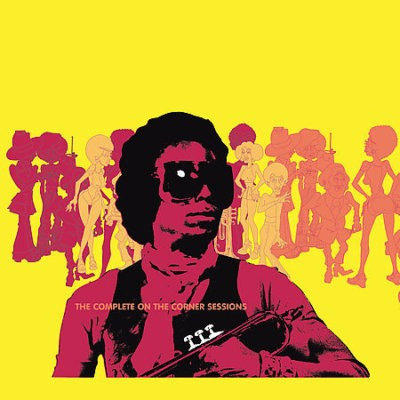

Miles Davis: On the Corner Fifty-one years later

If Bitches Brew was Miles Davis' Ulysses, On the Corner was his Finnegan's Wake

On the Corner is not a jazz album. Its influence is not in the jazz sphere. But it's also not a rock album or a funk album or anything else. With the sessions for this album Miles Davis assumed the role of a musical assassin, out to kill off the very idea of genre, and by association the idea of hybrid genres.

It is time to present the case that On the Corner is not merely an anomaly in Davis' electric catalog, a period that is always presented with a strong sense of embarrassment or apology, but rather the crowning achievement of a brilliant period of musical exploration.

Miles' music in the post-Bitches Brew electric period continued to change and develop into something else. By 1972 the developments of Bitches Brew had already been folded into Miles' subsequent music and he was looking for something new yet again.

Bitches Brew was a mysterious island where the sunset lasted for hours and morphed into a firelit night of dancing, worshiping and lovemaking. On the Corner was the sound of humid city nights when open windows offered little relief as the sound of sirens and arguments permeated the air.

In the words of Nate Chinen: "Sure, Bitches Brew had the revolutionary simmer, but On the Corner was what brought things to a boil."

If Bitches Brew was Miles Davis' Ulysses, On the Corner was his Finnegan's Wake

Miles had already offered up a couple of other records between these two. Live-Evil continued much of the Bitches Brew vibe and was a construction in the same way its studio companion had been. Tribute to Jack Johnson was a searing roadhouse set by a fantastic band with Davis prowling and jabbing with his trumpet and it brought guitar to the fore of Miles' band like never before.

Then came On the Corner, Miles' last complete studio album of the seventies by which time enough records had been released for Miles to drown out the sound of mewling, aging white men bitching about jazz this and jazz that, and hurtle in the direction that his talent and inspiration told him he must go, a gleaming rocket burning fuel at an ever accelerated rate.

With each record there is increasing volume, increasing defiance, as though to say, "What are you lame motherfuckers gonna do? You can't take back the shit I done. Can't take back Birth of the Cool, or Miles Ahead, Kind of Blue, or Sketches of Spain. Not Miles Smiles or Nefertiti or Sorcerer. They're all still there, lame mothers. But I'm here now, and what I'm doing is nothing to do with all that, and nothing to do with you either. Just leave it alone. And leave me alone too."

On the Corner is a missive from the future: the future of black music, the future of technology, the future of America, a future where you can fly your freak flag high and not give a shit. It's a unique artifact whose influence is both widespread and hiding in plain sight. It's a vinyl Rosetta Stone and its importance isn't how much people listen to it or that it's anyone's favorite Miles Davis album but rather in the way its DNA is all over so much that came along after. The tribal concrete techno noise that made the record so reviled when it was unleashed on an unsuspecting record buying public who had been indoctrinated into Bitches Brew only a short time before, is now just music.

The Beatles migrated from a typical British Invasion pop band to an influential studio rock band that rewrote the rules for how a band could write and record songs, perform, and market their music from 1963 to 1967. Miles did the same from 1969-75, going from a traditional but modern jazz musician to a cultural icon who was, in the words of Duke Ellington, truly 'beyond category.'

Like all music labeled 'experimental' when it is first heard, On the Corner sounds not so strange fifty years later, in part because we can now easily hear bits that remind us of other things we've heard--funk, EDM, hip hop, rock, fusion. Now the placement of On the Corner in the firmament of modern recorded music is much clearer to many more listeners, which is a sign of its success whether it is what Miles intended or not.

And there is some indication that the final release of On the Corner was not really quite what Miles had intended, but it turned out to be something that no one could probably have defined going into the project. There is a whole lot of everything in there--the dark, polyrhythmic bass and drum, Dave Liebman and Miles playing horns, electric guitar, Indian sitar and tabla, discordant sprays of organ, also played by Miles. It is in many ways the very definition of a musical collective, which is really what Miles' recording sessions had been for four years now. He entrusted the editing of these sessions into album sides to Teo Macero. In some ways it seemed as though Miles didn't really even have to be there, except that it was his energy that drove the sessions. His intermittent trumpet outbursts, whether clear as a bell tone or heavily wah-wah'ed, goaded the other players into the groove more fiercely.

Listeners and critics deeply underestimated the sheer force of will that it took for Davis to spark these records into being. Arriving at the studio with ideas and maybe a few sketches, an indication to Michael Henderson what the bass line should be like, Davis worked to inspire, scare, browbeat, psych out, and drive his musicians while Macero captured it all on tape. The raw material for what became the finished On the Corner album was completed in just three sessions and it was Davis' last proper studio album of the seventies as he concentrated on bringing his new music to live audiences.

In 1972 On the Corner was a missive from the future. In the 2020s, it is a Rosetta stone that helps decipher the language that was invented and pointed off in the many directions from which we view music today.

The point, at about eighteen minutes into the unedited master, where there is only the beat and the drone, is like an excerpt from a rave DJ set. Badal Roy's tabla plays a parade beat, joined by any number of street-derived noisemakers accompanied only by the drone of Colin Wolcott's sitar, heavily atmospheric. The track fades quickly, just as it faded in, and one feels this is music that could, and does, go on forever.

That is because, for one thing, there was only a very loose structure to what the group was playing. They weren't 'pieces' in the normal sense, but rather a set of guidelines that became specific pieces. As a result there weren't solos in the normal sense either. As in free jazz, the group ebbed and flowed such that at times a specific player would emerge from the sea foam and hold the listener's attention for a moment before being absorbed back into the group. It is the energy of the group, the forward motion of the collective, that defines the music of what I generally refer to as the On the Corner period.

As with all groups that rely on the moment to create the music that they are playing with little safety net, Miles found that the collective could not always sustain something interesting for an extended period of time. Sometimes the groove needs refraeshing, sometimes it seems Miles calculates how much repetition the listener will accept, and this is where Teo Macero comes in, editing pieces together to create a credible whole. But in live performances it was up to Miles, using musical and physical signs to the other players, to change the groove or decide what musician to bring to the foreground.

Throughout his career, Miles signaled a new direction on record before incorporating the new concept with his live band. By the time of On the Corner, though, Miles was already pushing beyond what was on the record in live performances. Some, like the one documented on Miles Davis in Concert: Live at Philharmonic Hall, are only middling in their results, while others, including Dark Magus and the final releases before his semi-retirement in 1975, Pangea and Agharta, go beyond the constraints of On the Corner's studio recordings.

It's important to acknowledge that On the Corner was a launching pad that rocketed Miles deep into outer (or inner) space in terms of his belief in the collective as a method of creating music that was more complex and organic than one human could conceive alone. But it's also true that sonically On the Corner is its own universe that was not repeated by Miles or anyone else yet spread its influence deep and wide.

No album is created in a cultural vacuum, and 1972 was an auspicious year for nearly every genre of recorded music. On the Corner takes the studio manipulation of Miles and Teo Macero and places it in the service of conveying the temperature of Black America at the time. For Davis in 1972, his contemporaries are not Freddie Hubbard or Chick Corea or Dexter Gordon but Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, and James Brown. Though his music doesn't sound similar, On the Corner is especially influenced by Sly & the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On in its sense of community, anger, disillusionment, and sheer force of artistic will.

TARGO stands in relation to its creator's place in musical culture in much the same place as On the Corner. It was widely rebuked at the time of its release, but has since been hailed as a significant record that influenced several musical genres (R&B, funk), as well as some which didn't exist yet (electronic, hip hop). It is a studio creation, so much so that it ceases to be a Sly & the Family Stone album, becoming instead a solo record with high profile special guests. It was created by someone who was so far out on the edge that their descent into both addiction and apathetic despair was, as they say, a sign of the times.

It's easy to see Miles in 1972 as being in a very different place than Sly in 1970, but in fact the two were in very similar places. Miles benefited by being subsidized, on a retainer from Columbia Records and able to book studio time whenever he wanted. Miles was kept more social by running a band, playing live gigs, and recording semi-regularly. But he was still an addict--addicted to pain pills that were prescribed to help keep in check the chronic pain of a bad hip and bad knees as well as to cocaine. The twin issues of chronic pain and the numbing effect of the drugs that were used to treat it led to feelings of despair and hopelessness just as surely as they did for Sly Stewart.

In fact, Miles was asked to go down to Sly's studio compound and see just what he was up to, and whether the Dark Magus could render some assistance in getting his album finished. Like Conrad's Marlow, Miles infiltrated the Stone compound and came face to face with the Mr. Kurtz of good time funk. In his autobiography, Miles spins it this way:

"The people at Columbia who own Epic--the label Sly was on --wanted to see if I could get Sly to record quicker. But Sly had his own way of writing music. He got his inspiration from the people in his group. When he wrote something he would write the music to be played live, rather than for a studio. After he got big he always had all these people around his house and at his recording sessions. I went to a couple and there were nothing but girls everywhere and coke, bodyguards with guns, looking all evil. I told him couldn't do nothing with him--told Columbia I couldn't make him record any quicker. We snorted some coke together and that was it." (Miles, The Autobiography, Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe, 1989, Simon & Schuster, p. 321)

The overall mood of the country was grim and downward. Young black people were experiencing the same thing as the white youth of the counterculture: the disillusionment of watching your hopes for a better tomorrow be co-opted and commercialized by straight society. It dawned on them that things were not going to get a whole lot better.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

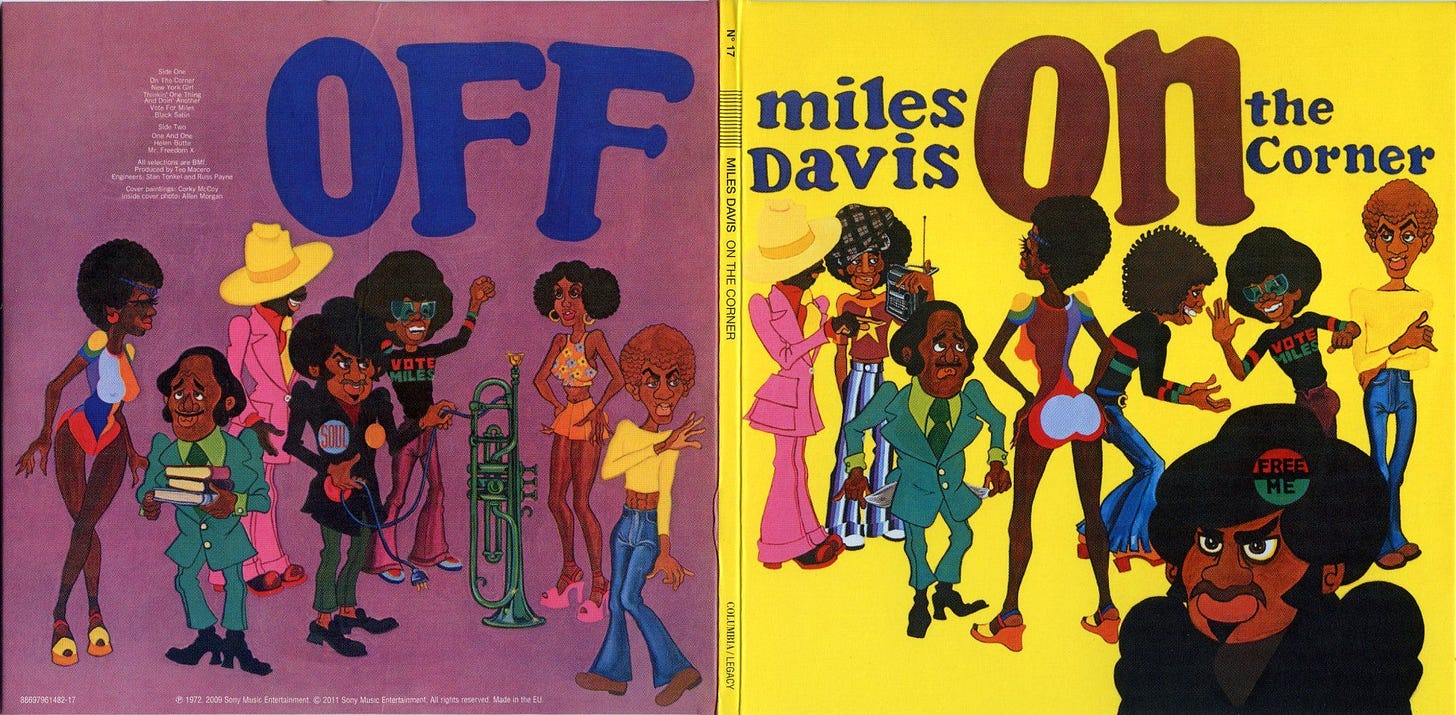

Great choice to write about, excellent analysis, Marshall. And it’s my go-to answer when someone on social media asks: “What album sounds exactly like its cover?”

Miles does not play organ on On The Corner. Hey began doing so on studio sessions and live shows shortly afterwards but none of the tracks from the actual album has Miles on organ.

Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Harold Ivory Williams, and Cedric Lawson are the keys players here.

Other than that, great write up!