Being a fan of Lou Reed was like having a special one way passport stamped for the cutout bins. A cult presence for most of his career, Reed would make a great album only to follow it up with what seemed, at the time, like a throwaway. At the very least he would change things up frequently enough to upset any group of fans who might have liked what he had just produced by stomping all over that shit with his next few releases. Rinse, repeat.

At some point you would ask yourself, 'why am I still a Lou Reed fan? Why do I still buy his records even though they confound me?' And inevitably Lou would pull something out of his backpack that would let you know why you were still there. On Coney Island Baby he pulled out the old 'glory of love' play, and here, on his next release, he's pulling out the old 'deep down inside/I got a rock and roll heart' play.

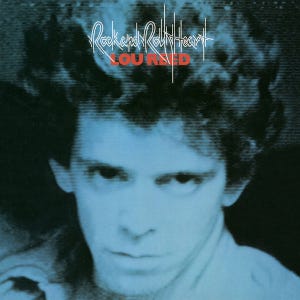

Lou put some effort into Rock and Roll Heart, and the result is maybe his finest record of songs in the rock and roll tradition since Loaded or his debut solo record. He had a new record label, Arista, who he wanted to impress. It had been four years since Transformer had made it seem like Lou could be a mainstream hit artist, like his pal David Bowie, and folks in the record industry were writing him off at an alarming rate.

Rock and Roll Heart definitely marked some new sonic territory. Reed had started working with pianist Michael Fonfara on Sally Can't Dance as well as some other musicians who were outside his normal rock and roll circle. They gave the music an uptown jazz feel, and Reed chose to dial down his guitar playing so that the keyboard and saxophone became the primary instruments. After the grand Wagnerian edifice of Rock and Roll Animal, Rock and Roll Heart sounded to some listeners like Lou lite. But it occupies an interesting space in this period of Reed's career, a period that most consider transitional, but which seems to have been pretty fully realized before he moved on to the next period.

For one thing, the album was the follow-up to Coney Island Baby, 'the Rachel album' where Lou mentions his live-in trans lover by name at the end of the title track, with the final intonation 'I swear, I'd give the whole thing up for you.' Not sure what he really meant--that he'd give up his career? The other fuck toys? The drugs? Alcohol? A grand, empty gesture. Because he never gave up any of them. In the end, he gave up Rachel and turned his back on that part of his life. He recorded Street Hassle, and buried the 'druggie fag shit' as he would have put it.

But in between, he made Rock and Roll Heart, and it gives the sense that Reed had found a groove. With a settled band, the record has more animus than Coney Island Baby and tracks like "Follow the Leader" pick up the R&B/NY Dance club scene that Sally Can't Dance evoked. It was an album that picked up the strongest elements of Reed's previous solo recordings and welded them together into a coherent program.

Even that cabaret aspect of The Velvet Underground represented by songs like "After Hours" is heard on "A Sheltered Life," a song that Reed wrote while still with the VU. It was tried out, but didn't gel at the time. Of course, Reed gets some ironic mileage out of the song's lyrics—"I've never taken dope/and I've never taken drugs/Never danced on a bearskin rug—" while the band gives it a swing it likely never previously had. Fogel overdubs tenor and soprano saxes playing counterpoint, giving a real New Orleans twist to the track. Cocktail music for the demi monde.

Especially since he bumps it up against the record's most 'outside' song, the final track, a dramatic monologue entitled "Temporary Thing." Set against a driving two chord drone, Reed confronts the lover/authority figure who has caught him in the act, or perhaps is staging a personal intervention:

You've read too many books, you've seen too many plays

And it's things like this, that turn you away

Hey, now, now, look, huh, look, hey look, hey look

You better think about it twice

I know that your good breeding makes it seem not so nice

Given the calm interface of the rest of the record, even when the lyrics are maudlin, "Temporary Thing" sticks out like a sore thumb. And it sounds a lot like the kind of songs that Lou will record on his next album, Street Hassle, particularly the song "Dirt" on which Lou rips someone a new asshole to the same kind of piano drone and drum/bass dirge.

Lou's vocal inflections are the thing that helps sell "Temporary Thing." When he growls, then spits out the word "bitch" it's hard to imagine the person who isn't going to back down from the implied threat. But there's a good bet that person looked a whole lot like Rachel Humphreys.

According to Michael Fonfara's quotations in Anthony DeCurtis' book Lou Reed, Rachel had a life outside her life with Lou, and that life involved a patina of violence and criminal activity. "I never put Rachel down" said the keyboard player. "Rachel and I were good friends. But Rachel had an extra life in addition to the one she lived with Lou. And that was the drag-queen-on-the-street life. [Lou] knew how tough she was. He knew how good she was with a knife."

The opening song on Coney Island Baby, "Crazy Feeling" sounds like it could be a recounting of the first time Lou saw Rachel:

You're the kind of person that I've been dreaming of

You're the kind of person that I always wanted to love

And when I first seen you walk right through that bar door

And I seen those suit and tie johns buy you one drink

And then buy you some more...

Both Coney Island Baby and Rock and Roll Heart are stocked with songs about trade and the nature of relationships in what is now defined as LGBTQ+, but at the time was a much more fragmented community.

It opens as a party album, with Lou assuring us he still "Believes in Love" lest we forget how Coney Island Baby concluded. But the whole vibe is loose and good-timey, like a drunken Saturday night on Christopher street while the band gives new life to Lou's latest take on the three chords that defined his unarguable classic song "Sweet Jane." I mean, Lou was pulling out the whole 'rock and roll heart' thing way back then. And he opens so many records with a variation of that, his harmonic version of the Bo Diddley beat, the signature being not the beat, which is variable, but the three chords themselves. When he doesn't open a record that way, something is up.

Next is "Banging on My Drum," which is one of those songs that just kind of creates itself out of drive and dust, reminiscent of such Lou delicacies as "I Can't Stand It" or "We're Gonna Have a Real Good Time Together." And even if you find the title track to be rather cheesy and awkward in its sentiments (which it is), "Banging on My Drum" is a song that demonstrates the beating heart of rock and roll that Lou harbored until his last breath.

Next up is "Follow the Leader," which churns with NYC club/disco rhythm and some soulful tenor sax. Michael Suchorsky's skittering snare work mimics Lou's stuttering vocal as he urges the listener to sweat, dance, and find some romance. At this point the album definitely seems a bit lightweight, but Lou is about to check in with some major songs.

"You Wear It So Well" starts with a piano intro that sounds like it could easily have come from Berlin. Fogel's influence on the track is undeniable. He's there, bubbling beneath the surface on the intro, and when the song kicks into gear hes's deep into the lower registers of his saxophone, providing support to the song's wobbly structure, it's tonal quality mimicking a cello at times.

Lyrically, the song is simple Reed Zen. With all of the stories you have to tell, he tells his listener, you wear it so well. With all that you have seen and done, you wear it with grace and dignity. But there's also a downside--your face hides it so that we can't see your inner pain. And as the song progresses, we celebrate not the endurance with grace but rather the deliberate hiding of pain. As Reed repeats the title phrase, he plays with the other lines of the song--the grace and style vs. the hiding and the pain--over the background of his vocals backed by longtime friend Garland Jeffries, until it becomes a Van Morrison incantation, achieving meaning through repetition, like a mantra.

Next is another slower tune, "Ladies Pay," opening again with Fonfara's piano. It took me a while to understand that this is Reed's most piano-centric record to that date. The guitar is not in the forefront of most of these songs, though on this track the guitar line provides a stately counterpoint to the piano part. Can't help but notice the way this track reminds me of the Patti Smith Group cut loose: the swirling piano, increasingly aggressive guitar, the rhythm section eventually bursting into a straight ahead rock gallop--reminiscent of Smith's "Free Money."

The title track announces the end of Side One with roaring 'Sweet Jane' guitar chords, but after the intro, it backs off and once again the main instruments are acoustic piano and clavinet. Verse, chorus, just like that. But then, there is this middle eight, which adds little lyrically ("Just a rock & roll heart/searching for a good time") but musically it gives the song legs as Fonfara's organ rises out of the mist to carry us through and then BAM! It's back to the roaring guitar. Not much of a song, some might say, but this is what saved Jeannie's life when she started dancing to that fine, fine music. Lou for the win.

Side two starts with an instrumental, the only instrumental I can recall in Lou's catalog (Metal Machine Music notwithstanding). It's swirling opening features Marty Fogel's sax and summons a smaller version of the sonic stew that the band will help Reed create on "The Bells." Then it settles into a folk rock groove with Reed on acoustic guitar. It sounds like a song Reed just didn't get around to writing lyrics to. And it has the title 'Chooser and the Chosen One' that maintains that theme of who is top and bottom, who is trade and who is not, who controls the scene.

The rest of the side unfolds with a seeming internal logic, the songs pretty good, the band selling them very well and Reed's enthusiasm putting them over the top. "Senselessly Cruel" is about how a girl at school was cruel to him but he is no masochist. No, he has toughened up and won't be treated badly again. "Claim To Fame" is a rocker that sounds like it could have been written for his first solo record with its talky-druggy-singsong:

Get it up and get it back

making it upon your back

No space, no rent

the money's gone, it's all been spent now

tell me 'bout your claim to fame

Reed could be talking about himself here, he could be talking about Rachel, he could be talking to Bowie or Iggy or some imaginary adversary. But the thing here is that it doesn't matter, it's a great song and a great performance. This is the band that will see Reed through the next few albums and some important parts of his long career, and you can hear them settling in, and Reed's comfort level with things is telling.

"Vicious Circle" is a beautiful Reed kinda ballad that follows a more or less standard format and Reed's acoustic guitar sounds great bolstered by Michael Fonfara's sustain-heavy electric piano. This mellowing of energy sets up the Wiemar-era cabaret number "Sheltered Life" with Lou as the smiling MC, mocking his upbringing, his family, his reputation. So flip, so light, how perfectly it sets up the bitch slap of "Temporary Thing" that ends the record.

Reed and the band toured behind Rock and Roll Heart, and Reed mounted a multimedia presentation with the help of Mick Rock. The two, along with guitarist Jeffrey Ross, found old televisions in the street and in service shops or wherever, and stacked these behind the stage, then Rock would feed images from backstage into the monitor, bathing Reed in an eerie glow of images.

But Rock and Roll Heart didn't sell well. The critics were suspicious of Reed's conversion to a jazzier sound after so many previous put-ons, or so they thought. I really don't think that Lou was purposely putting anyone on most of the time. He had a deadpan sense of humor and a big mouth and also an unorthodox sense of the ethereal beauty of melody. The fans were confused, as usual.

When Rock and Roll Heart hit the cutout bins, I would have been in high school, probably barely. I was already a big Lou Reed fan, and a lot of my Reed albums came from used record stores, but I picked up Sally Can't Dance in the cutout bin as well, and the VU live double album and Live at Max's Kansas City. For a long time I was likely affected by received wisdom on Lou's albums, and I always considered Rock and Roll Heart to be a fairly minor record. But I also recall that whenever I put it on the turntable, I fell under the spell of Fonfara's electric piano and Marty Fogel's saxophone as well as the free form, kind of aimless sense of some of the songs. Song for song, I'm not at all sure that it doesn't sound better today overall than Transformer, which, after all, was about a moment in rock history, the ascendancy and brief reign of glam rock. Such is the luxury of becoming intimate with the unpopular, unsold titles in an artist's discography that the cutout bins afforded.

As a paying subscriber, you can comment on My Life in the Cutout Bins drafts published here. This series will be the jumping off point for the creation and publication of a book of these essays in the next year or so. Your comments regarding specific pieces or the project as a whole are welcome.

I thank you deeply for your support of New Directions in Music and my research/writing about popular music. You help keep the lights on, the turntable functioning, and the cats fed. Please let your music-loving friends (you know who they are) know about New Directions in Music, as it’s the best way for me to keep on delivering value to those for whom the music is a way of life.