Arthur Rimbaud wrote all of his poetry by the age of twenty, at which point he went silent, moving to Abyssinia, otherwise known as Ethiopia, where he became a successful merchant, a trader and sometimes arms dealer. His somewhat mysterious life and early death at age 37 all but insured that he would become influential in the rock and roll era.

And certainly he influenced few artists more than Patti Smith. The high priestess of rock poetry made no bones about the influence of the French symbolist poet on her debut album, Horses in myriad interviews done in its wake. Robert Mapplethorpe's cover portrait presented Patti as a modern day, genderless Rimbaud.

As a budding writer, I dabbled more than a little with poetry, and so I found myself in a local mall bookstore searching a poetry section that included Suzanne Sommers for the work of Arthur Rimbaud. I came up with Complete Works, a Harper Collins paperback, and I read Rimbaud's poetry voraciously, though I enjoyed Baudelaire, who Rimbaud considered rather pedestrian, more.

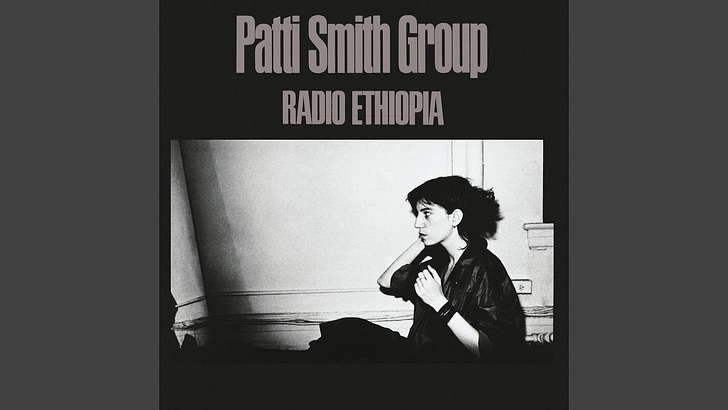

I had fallen completely under Patti Smith's spell as soon as the needle dropped on Horses. So of course I jumped at the chance to purchase her second album, Radio Ethiopia, as a classic notched cutout bin special. With its bold black cover and black and white portrait of Patti, it felt like a monolithic and forbidding album, something akin to White Light/White Heat. The rap on the album was that it was disappointing: it lacked focus, we'd heard it already, the title track was a space-filling guitar squall accompanied by largely incomprehensible poetry, it was too precious, lazy, and indulgent.

Time in the cutout bins had already taught me that feedback like this was de facto evidence of the need to closely listen to the album in question. When so many people are dismissive of a record, there are really only two possibilities. One is that they are right. Obviously the cutout bins are full of tricks, traps, flirts, and outright frippery: the false steps and mistakes of artists and the labels that supported them. But the other lesson learned in the bins is that one man or woman's trash is another's trinket. The cutout bins are like a shadow of the more expensive part of one's record collection. Few of my purchases represent the artist's best work, but in many cases I developed a close relationship with the cutout albums I bought and they informed my relationship with the artist as a whole.

Radio Ethiopia is a continuation of the idea, presented on Horses, of rock and roll music as ritual. The connections between garage rock, primitive art, symbolic poetry, the life of a street tough, and religious impulses are all drawn together in a fever dream of ecstatic electricity. It's a pretty great album, and there are times when I definitely prefer to hear its outright guitar centric rock and roll assault to Horses. Radio Ethiopia is credited to The Patti Smith Group, as were her next two releases before her semi-retirement, Easter and Wave. Horses was credited to Patti Smith alone, though the group is pretty much the same.

We open with "Ask the Angels," a call to arms, as dark forces marshal themselves across the world--'world war is the battle cry.' Smith's assertion that the time is 'wild, wild, wild, wild' is not merely a rock and roll party cry. It raises the prospect of real terror in a time of chaos. The wolf is not just at the door, but his jaws are dripping with the blood of his conquests. And so it is time to take up guitars and raise our voices once again. Ask not for whom the angels call, babe, it's for you.

Then comes "Ain't it Strange," one of the album's highlights that had also become an integral part of Smith's live performances. A primitive, hypnotic guitar line wends its way along a path created by an almost dubby bass and drums, as Smith intones the song's opening lines: "Down in Vineland/there's a clubhouse..." Her vocals become more intense as the song builds. You can almost smell the billowing clouds of incense, feel the humidity of the fetid river that flows nearby, and sense the rhythms carry you away, downstream, like Marlowe heading inevitably toward Kurtz. Patti prays, chants, and speaks in tongues: "Will you go to the temple tonight?'/No, I don't think so, no..."

Live, “the song had become a shamanic ritual,” according to Will Hermes, author of Love Goes to the Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever. “Smith spinning like a Sufi, Kaye engaging her in what he called a sort of ‘ballet’ during the song’s shape-shifting second half. At one of the November Bottom Line shows, Smith chased Kaye through the crowd during the song, walking across tables, knocking over drinks.” Things came to a head near the end of the year at a show in Tampa where, spinning uncontrollably, the singer fell fourteen feet from the stage, breaking several vertebrae. Doctors were doubtful that she would perform again, but she did recover, releasing Easter in 1978.

"Poppies" is about the interactions of pleasure and desire, dream and reality, and it has a groove, though a bit faster, that is similar to that on "Dancing Barefoot" on Wave. Patti's voice is layered, weaving poetry and incantation around the lyrics in a manner that was used on Horses and also on "Kicks" from Lou Reed's Coney Island Baby, released the same year. Performing at The Bottom Line in 1978 Reed called out from the stage, "Fuck Radio Ethiopia, man, I'm Radio Brooklyn" to thunderous (well, for a 400 seat venue) applause. But someone in the audience isn't pleased. You can hear them yelling back "Patti Smith!" Reed followed up his comment with "I ain't no snob, man." It's more likely that Reed was irked with Smith's occupation of the cultural spot that he truly coveted--artist, poet--than that he truly objected to her more artistic pretensions. It's a bit ironic that Lou's next album, The Bells, would mirror Radio Ethiopia in some ways, with a title track of ambient free jazz over layered poetry.

Next we get 'Pissing In a River,' one of Nick Hornby's songs that most influenced his life, a song of which he writes: "its emotional effects depended entirely on its chords and its chorus and its attitude." Which is as good a description of rock and roll as any. Patti collaborated on all the songs on Radio Ethiopia. One of her biggest collaborators at the time was PSG bassist/guitarist Ivan Kral. Kral was born in Czechoslovakia, coming to the United States with his family as a refugee in 1966. He became a U.S. citizen in 1981, a fact alluded to in the song "Citizen Ship" from the Wave album.

Kral was a frequent songwriting collaborator with Smith, playing bass and at times being what Lenny Kaye referred to as "my guitar brother in the group." He helped shape the band's improvisations and contributed a signature minor key trance vibe to some of the group's songs, including this one. The band had become heavier, providing some of the energy of metal bands of the time while avoiding the genre's instensive monotony--a characteristic that Robert Christgau commented on. The group's sound is in many ways reminiscent of that of Blue Oyster Cult. Alan Lanier, the keyboard player with the band, was Patti's boyfriend and occasional songwriting collaborator at the time, and Smith contributed lyrics and a few vocals to some of their albums, including Agents of Fortune and Fire of Unknown Origin.

There are times on "Pissing in a River" that sound like a smaller E Street Band in the clarity of their arrangement and the obvious commitment with which all of the band attacks the song. Springsteen attended some of the Bottom Line shows promoting Radio Ethiopia, and of course Patti later recorded her lyrical rewrite of Bruce's 'Because the Night.' You can hear the influence on Bruce's Darkness on the Edge of Town album as well, before the edges got sanded down for The River.

Side Two opens with a punk barn burner that could easily have come from Horses. "Pumping (My Heart)." One can imagine this was an expected FM radio single from the get go. That's followed by the plaintive, imploring "Distant Fingers" written by Smith and Alan Lanier. It has a vague reggae feeling to it on the verses and a melodic bridge that recalls street corner singing and old rock ballads. The remainder of the record is dedicated to its title track and the brief coda "Abyssinia."

In February 1891, Arthur Rimbaud began to experience pain in his left knee. As it continued to deteriorate he left for France to seek treatment: "Sixteen porters carried him on a hidebound stretcher to the port at Zeila, 200 miles and 12 days from Harar. It was the same port where Rimbaud had first set foot in Africa, 11 years earlier." https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/01/travel/where-rimbaud-found-peace-in-ethiopia.html

At the hospital in Marseilles his leg was amputated. He spent August at his family's farm in Roche before departing to return to Ethiopia. "I hope to return there [to Harar]" he wrote. "I will always live there."

Unfortunately he fell ill again on the way and was re-hospitalized, dying on November 10. He died of osteosarcoma.

This story, of Rimbaud's attempts to return home to Ethiopia where he had made a spiritual home for himself, of the feverish dreams of a dying man in excruciating pain, is the subtext of the ten minute improvisation by Patti Smith and guitarist Lenny Kaye and the coda, "Abyssinia" which follows. Following a Lenny Kaye guitar cadenza the band settles into a tribal riff beat and Smith spits out her opening gambit: "Oh I'll send you a telegram/Oh I Have some information for you..."

Patti's lyrics offer the same sweeping condemnation of the mediocrity of the French life he left behind for Harar as Rimbaud's own poetry, exhorting the life he found. In 2000 the Arthur Rimbaud Cultural Center was opened there, and according to its curator, Abdunasir Abdulahi, “young people are starting to believe Rimbaud was really a white man who loved Hararis, who wanted to die in Harar, who preferred Harar to his sophisticated, nationalized Europe. His mind was peaceful here."

The band riffs heavy, loud, and primitive in true garage rock fashion, but it sounds quite different under Jack Douglas' production than John Cale's. Douglas had developed a very close relationship with Aerosmith, producing Get Your Wings, Toys in the Attic, Rocks, and Draw the Line. He would go on to produce sessions for John Lennon & Yoko Ono's Double Fantasy record. On Radio Ethiopia Patti seeks refuge in the sangha, her band, and she finds it throughout the record and especially during the climactic sequence of the title track:

"As for you you do as you must

But as for me I trust

That you will book me on the first freighter

So I can get the hell out of here

And go back home to

Abyssinia"

Leading straight into the final two minutes, titled "Abyssinia", with Kaye's subdued washes of guitar feedback over Smith's poetry.

For the 150th anniversary edition of Rimbauad's Une Saison en Enfer, Smith devised an exhibition and catalog of the work that incorporated her own documents, drawings, photographs, and poetry in order to demonstrate the heavy influence of Rimbaud's poetry on her own work throughout her career. In retrospect, it seems as though Radio Ethiopia was her most direct channeling of the French poet's spirit, a rock and roll séance of sorts.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

Great read - even if I did cheer myself (in my living room) at Lou's snark on Take No Prisoners!