It's 1976. Ray Davies and The Kinks have spent the six years since their last American hit records, "Lola" and "Apeman," in a haze of dodgy concept albums that, while interesting in their own right, were an increasing source of alienation to the average record buyer and former Kinks fan. Not to mention the band, who insisted on a return to some semblance of a rock band for their final MCA album, Schoolboys In Disgrace. Of course, that had nary a hit, and so off the roster went the lads from Muswell.

Enter Arista Records, run by Clive Davis in his post-Columbia resurrection. A label needs solid talent, but Arista wasn't in a place to buy some of the names they might have liked. When Davis created Arista from the ashes of Bell Records, he kept only two acts on the roster: Barry Manilow, and Melissa Manchester. Manilow turned into a cash cow for the label, and Manchester had a respectable career as a recording artist and as a songwriter of note, but of course more established acts were needed.

Arista became expert at signing artists whose previous label was happy to see them go (Lou Reed, Iggy Pop) and encouraging them to record albums that would result in hit singles, or at least profitable sales and live tours. The Kinks fit this description like a glove. They still had a certain cachet as an original sixties British Invasion group, but that was fading to the nostalgia tour area by the time they signed with Uncle Clive. The label made it clear that they wanted a record of fresh rock songs unencumbered by a story or a concept or a screed against moralists and the educational system.

So Ray decided, instead of being relegated to the dustbin of rock history, he would relegate himself to playing larger concert halls, playing music that was punchier, louder, and very audience friendly to Americans who had no idea what the group had been doing since "You Really Got Me" or, if they were lucky, "Lola." The Kinks would record their next record on a brand new 24 track recorder recently installed at their Konk studios, giving them a contemporary sound and big studio gloss that had eluded them for many years.

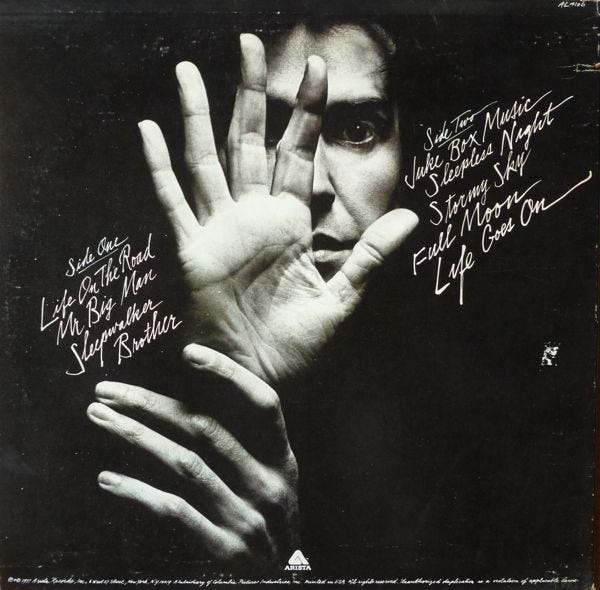

To entertain the masses, Ray writes some songs about his life as a rock musician, in and around the music business, turning inward a bit. He's got a total of maybe thirty songs knocking about, and in May of 1976, the band goes into the studio and ends up making attempts at nearly twenty of them. A few, like "Power of Gold," "Stagefright," and "Restless" are rejected. Through the summer, a number of songs were recorded, though many of the recordings were later rejected and re-recorded. These included "Life on the Road," "Brother," "Juke Box Music," and two songs that were held back and included on the follow up record, Misfits--"Hay Fever" and "In a Foreign Land." Still more tracks were used as B-sides or fell among a second group of rejects.

Certainly this represented a strong effort on the band's part of come up with a solid album. The last proper record featuring new songs that wasn't a dramatic concept album or elaborate musical was half of 1972's double LP Everybody's In Showbiz, with the second record being live. The last regular Kinks album as a rock band had really been 1971's Muswell Hillbillies.

Ray starts off Sleepwalker with an almost McCartney-esque conceit. He writes a music hall intro about wanting to get out of town and see the world before the band kicks in with a mid-tempo boogie and we hear Davies' story about hitting the big city and living the life of a hustler and spiv--or a rock musician. There is a certain amount of weariness, but after all, he says "I'm living the life that I chose."

Next comes "Mr. Big," in which Ray takes the time to excoriate successful stars who become too big to acknowledge old friends--a cautionary tale? It's the only track without bassist John Dalton, who quit the band during the sessions and was replaced by former Bloodwyn Pig member Andy Pyle, who played on Misfits and on tour.

Side one, track three and we've reached the title track. First, this operates on a guitar riff that is reminiscent, as so many are, of another Kinks song you've already heard. In this case, to my ears, it's based on a riff that is similar to that of "Where Have All the Good Times Gone?", however the beat is completely different, similar in its groove and its energy to Steve Miller Band's "Take the Money and Run," out around the same time. The lyrics are a little off-kilter, though. After taking us into his confidence and letting us know "Everybody's got problems, buddy, I got mine," the narrator confides that 'When the sun turns out the light/I join the creatures of the night." The song veers between portraying Ray's narrator's simpatico with people who can be found in the shadows--sleepwalker, night stalker, street walker, night hawker--and hinting at something more kinky and sinister, like being a vampire or maybe a sex offender or serial killer.

"Sleepwalker" is not the only song on the album where Ray Davies contemplates the strangeness brought on by the night. Side Two's "Full Moon" finds him telling a possible paramour, "Don't be afraid of me when I'm walking in my sleep/Don't get alarmed, dear, when I start to crawl and creep." It reminds me of nothing so much as the hapless lord of the manor in a Hammer film who is subject to some family curse of which his wife knows nothing.

"You see before you a truly broken man/'Cause when it gets to midnight, I don't know who I am." There's the werewolf allusion there, the horror show in which our hero turns into something he has never seen, yet somehow always knew was there, lurking beneath the surface, but because it's Ray Davies, there's more. It's about losing his sense of self, of wondering who he is and what he's doing and whether any of it matters anymore.

In the film From Dusk Til Dawn, Harvey Keitel's character, a minister who questions his faith, has this monologue: "I don't care if you're a preacher, a priest, a nun, a rabbi, or a Buddhist monk. Many, many times during your life you will look at your reflection in a mirror and ask yourself: am I a fool?" This is where Ray Davies finds himself some fourteen years into his rock and roll career. Sleepwalker and Misfits, released in 1977 and 1978, are informed by the death of Elvis Presley and finds Davies wondering if he isn't just wasting his life away. On Misfits' "Rock and Roll Fantasy" he sings of the fans for whom the Kinks music is everything, for whom the music is both a welcome escape and a passive excuse for not getting their lives together. On Sleepwalker, it's the energetic "Juke Box Music," which leads off Side two and talks about a woman for whom the records are her reality while the chorus maintains that "It's only Jukebox music/only jukebox music."

Taken together, I think that the two records constitute a midlife crisis for Mr. Davies and his response is both to analyze his life and to celebrate making music with his brother and bandmates again, music that is a powerful part of their recorded legacy. Dave Davies plays guitar with all of the magic and power that made him the envy of every British invasion band. Good contributions, also, from drummer Mick Avory and keyboard player John Gosling.

The final track of side one is the power ballad "Brother" which preaches unity and a sense of compassion. It has one of those searching, vulnerable, lifting melodies that Davies is so expert at constructing, but it ends up being rather dull overall. Clive thought the track should be released as a single. To him, it had a similar vibe and spiritual approach to 'Bridge Over Troubled Waters.' I have to admit that I just don't hear it. It feels like a huge momentum blocker, and I wonder that there wasn't a better track from the things they had recorded or taken a stab at that would have served this album better.

"Jukebox Music" returns the energy level before handing off to "Sleepless Night," a minor key rocker wherein our narrator can't sleep because his ex-girlfriend who lives next door is having great sex all night long. 'She doesn't want me/but she won't let me be.'

"Stormy Sky" sounds like a song from one of those Time Life soft rock collections, maybe a track that you forgot about by Little River Band or Orleans. The gorgeous electric piano, processed guitar and vocals sounding like the time just before the time before dusk. It always seems like music you should be listening to on an airplane, floating high above the clouds.

I want to address something about these late seventies Arista albums, which is that when they are reviewed the topic of 'processed' sound, or 'production choices' invariably arise as an implicit criticism of these records. There is no question that these records don't sound like the records of the early Kinks, nor of the early '70s records that followed. That follows, at least in part, from the use of 24 track recording for the first time as well as the commercial needs of the record label. The band began to use a more compressed production moving into the eighties, but those records begin to sound more like the big beat stadium rock of Bon Jovi or someone comparable, giving them their own 'processed' sound. All recorded music is dated by the time of its recording, the available technology, and so forth. It can diminish one's enjoyment of a record if it's a sound you don't like, but it doesn't make decent music bad.

As far as Davies' songwriting, there are times when it seems more like a stylistic exercise than any real statement, but overall the songs were no worse, and in many ways better, than the stuff on Preservation Act and Soap Opera. As I've mentioned, the only track that I would swap out is "Brother," and that's admittedly a purely personal choice.

On the final track, "Life Goes On" Ray begins a tradition that will stick around for the rest of the group's time with Arista--he goes philosophical but puts both humor and a certain vocal tenderness into service, not to mention his considerable talent for writing a melody that catches the ear in a way both nostalgic and wistful. The Davies brothers play warmly layered acoustic guitars, and Dave plays a well constructed electric solo, his Gibson Les Paul Artisan ringing out. The song came up in a 1990 interview Dave did with Guitar Player:

"With "Life Goes On," we sat down and Ray just started playing it. It was the song that was really important: the emotion it created, the hollowness of it, but the fullness, as well. Those kinds of things really get me going. It just came out, because it was still that period where you could go into a studio and make a decent recording in a couple of days; you didn't have to spend three weeks just trying to get a sound on a drum computer. You could actually go in and do a song and the solos at the same time. I play off Ray's vocals, the way he expresses himself. Although I love guitar, it's still only an instrument that should help the song. That's my musical role, in a way."

It's amazing how strongly this track emits a positive vibe of enlightened contentment with the workings of the universe at their darkest. A song about suicide, really, but also about perseverance and staying the course. It's the perfect closer, leading both back to the introspection and sense of fate of the opening "Life on the Road" as well as forward, to the title track that opens the Misfits album.

A midlife crisis never sounded so good, but you'd expect nothing less from The Kinks.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

Funny, but those dodgy concept albums were my introduction to the band. It didn't stop me from enjoying the more audience friendly albums that followed. But I do find myself returning to the early 70s stuff more often.

Great appreciation of a great album. Sleepwalker is by far my favorite of the band’s Arista period, and I actually love the way the production on this one sounds; Misfits sounds good to me too, but the track listing is much patchier.