Pedro Bell: Art in the Service of the Groove

Remembering the artist, who created the visual aesthetic of George Clinton's best work

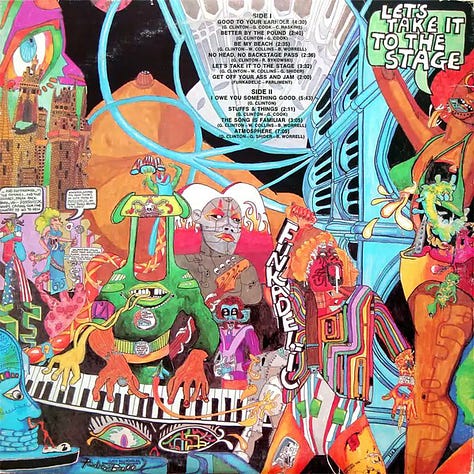

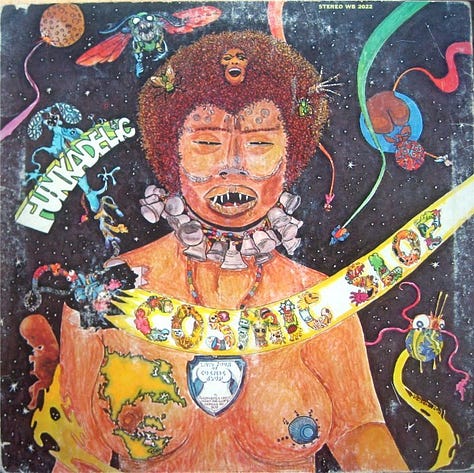

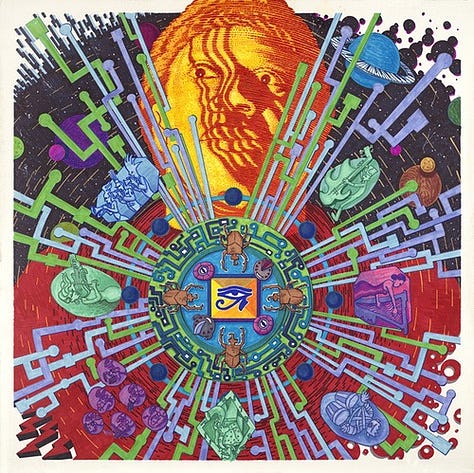

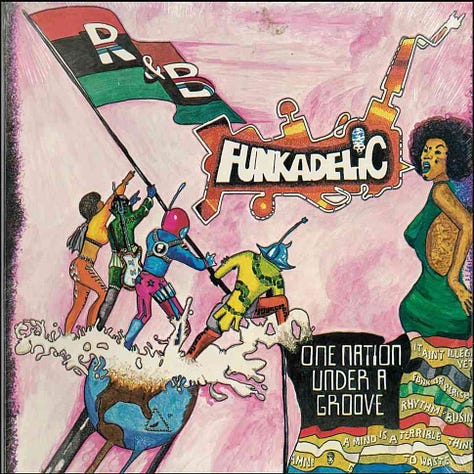

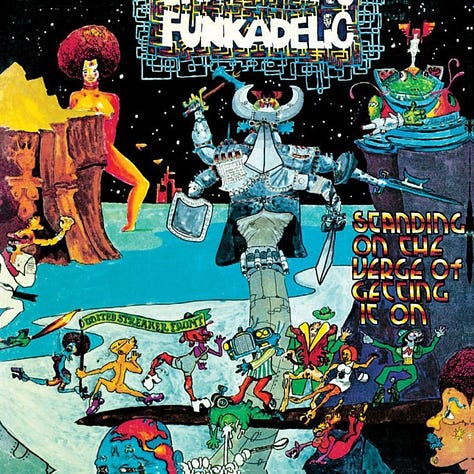

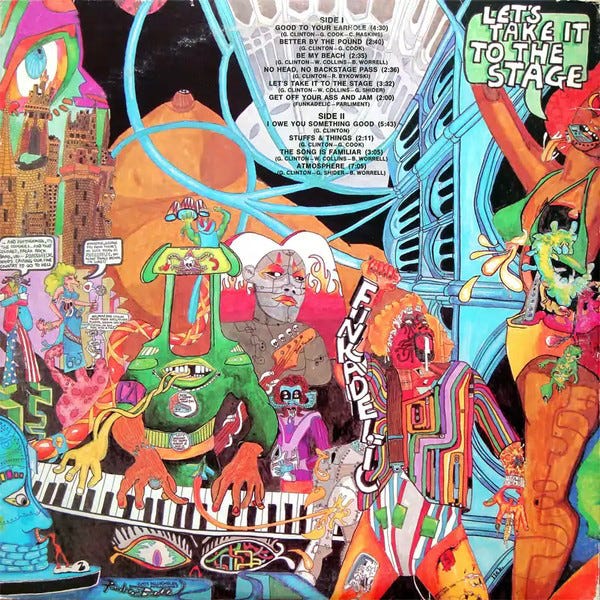

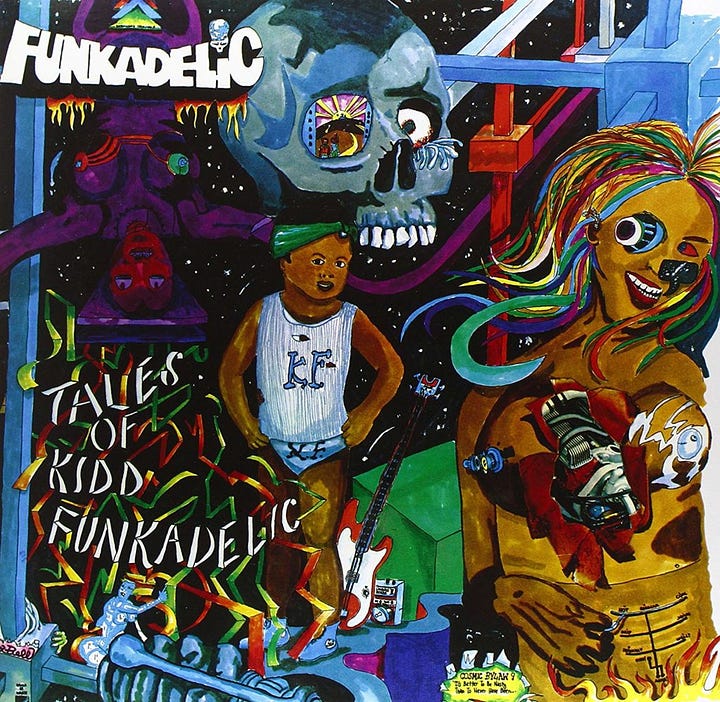

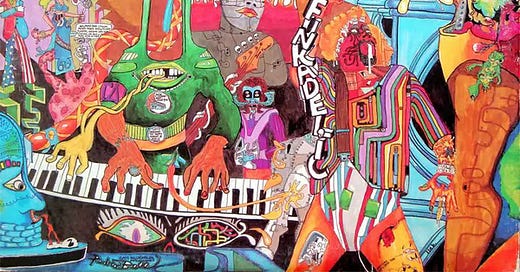

Pedro Bell, also known as Sir Lleb, the Maggot Minister of Funkdelia, was an original and major talent. Bell is known first and foremost for his brightly colored, cartoonish art that graced the covers of such classic Funkadelic albums as Cosmic Slop, One Nation Under a Groove, The Electric Spanking of War Babies and many more. But he was much more than the band’s cover artist.

Bell also penned liner notes to many of the albums, expanding on George Clinton’s ideas and concepts and contributing many of his own ideas to the band’s Afrofuturistic mythology. Like Clinton, Bootsy Collins, Bernie Worrell and other members of the Funkadelic entourage, Bell lived the Funkadelic lifestyle, which included dressing in psychedelic clothing and smoking marijuana.

“I talked through ‘Cosmic Slop’ with Pedro on the telephone, and his mind translated it into a strange vision told in half-visual and half-verbal language. When he sent us his interpretation I was blown away. It was nightmarish and funny and beautiful, a perfect fit for the music.”

-George Clinton-

In fact, Bell is a key connection between the space mythology of Sun Ra and the development of the Afrofuturistic perspective that has continued to develop and gain momentum over the past decade. Growing up in Chicago, Bell had the opportunity to see Sun Ra in 1958, an experience he dubbed “pretty deep for my creative.” The underground comics of the 1960s proved to be very inspirational to Bell as well, and he has always cited the work of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth with its custom car culture and odd characters as a strong inspiration. Other sources included Abbie Hoffman’s counterculture text Steal This Book with its R Crumb illustrations and the often surreal covers of avant rocker Frank Zappa.

After hearing an early Funkadelic track on local radio, Bell began to create artwork based on their sound and sent it to their Westbound Records label in Detroit. By 1973 George Clinton had paid young Bell a visit in Chicago and soon he was part of the group’s stable of talent, creating drawings and cartoons based on the band’s records and his own inspiration.

“Premature ecological doom through the reactionary efforts of POLLUTING ENTERPRISES of capitalistic pimpism foreshadow Earth’s demise. These cachetic mumruffians of madness continue to hasten total biological Armageddon for the ‘benefit’ of consumerism. And WITHOUT SHAME–decare their eventual victims as the bangling argie-bargies responsible for the ecological pimpster game that they cheerfully continue…AWAKE NOT, and Earth remains as this solar system’s space strumpet…sour milk from the breast of MOTHER NATURE!”

–From the liner notes for Cosmic Slop–

George Clinton’s P-Funk collective was an entire mythology and Pedro Bell essentially created the visual brand for the project, incorporating his beloved underground comics, radical politics, ironic humor and science fiction. The best way to view his work is on original vinyl album covers where you can be sure that previous owners spent a lot of time looking at every detail, reading every joke, realizing that they could forge a new identity where being black was taken as a given and a positive aspect of life.

Keep in mind that this was all before MTV, before the Internet, before Instagram and the other hordes of social media that can now put a band’s music, image, and overall brand identity in front of a potential international audience 24/7. In inner city America of the 1970s the sources of information were the nightly news, the daily paper, the radio, and the street. Funkadelic wasn’t going to get any play in the mainstream (white) media. But their music began to appear on the shows of the hip underground DJs who worked at local radio stations and Bell’s images made sure that the band’s music and image spread through the street.

Funkadelic records were holy grails of community, serving as entertainment, political broadsides, and the reminder that however oppressed you felt, there were folks like you everywhere, people ready to let their freak flags fly because they are One Nation Under a Groove–not the USA, but a subnation of colorful crayons that were not going back in the box.

In Bell’s wake the album covers of the hippest black artists began to change. Miles Davis’ albums moved from the Afromythology of Mati Klarwein to the urban cartoons of Corky McCoy. Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters album featured a recording studio VU meter turned into an urban tribal mask. It would only be a handful of years before Keith Haring and other urban street artists, many of whom were profoundly influenced by Bell’s work, began to make a dent in the mainstream cultural landscape.

In the 1980s things got more difficult for black urban communities in the wake of Reaganism. George Clinton dissolved Parliament and Funkadelic as recording entities but continued to release his own albums, and Bell created covers for those as well. But although some of Clinton’s albums sold well (Computer Games spawned the hit single “Atomic Dogs”) Pedro Bell had never made any real money from his work. It’s not so much that he didn’t get paid, but he always needed to work other ‘day jobs’ completely unrelated to his work as an artist. It’s safe to say that he was never compensated properly for not just the album covers themselves but for his cultural contribution to the Funkadelic legacy.

Bell kept on creating, working on a few non-Clinton album covers and even created his own animated Larry Lazer cartoon for MTV. But the music industry was changing and CDs became the new medium of music distribution. Cover art was reduced to the size of a pocket square and there was no work. Bell began to experience health problems during the 1990s and a 2009 Chicago Sun-Times article found the 59 year-old artist living in an SRO on Chicago’s south side, undergoing regular dialysis treatments and slowly losing his eyesight.

Bell did begin to receive some recognition from the art world, his work included in shows at galleries in Canada and the U.S. and as part of the MCA exhibit “Sympathy for the Devil: Art and Rock ‘n’ Roll since 1967,” which toured the country. With assistance from family and friends who staged a benefit for the artist, he was able to find affordable assisted living arrangements. Eventually losing his eyesight completely, Bell sold many of his original works to galleries and collectors.

In the words of Pan Wendt, who with Luis Jacob curated a 2009 exhibition at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery in Toronto called “Funkaesthetics” that included Bell’s work:

“The artwork of Pedro Bell was an essential component of the alternately utopian and dystopian world of P-Funk, which placed African-American reality in the context of a science fiction future that was both scary and hopeful.”

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

Smart work again, Marshall. Pedro Bell's art for P-Funk records was as close an approximation of visuals-as-music as anyone who did album art, with the possible exception of the photo/filter of the Beatles' "Rubber Soul" cover. He should be as well known as the street artists he no doubt influenced, such as J-M Basquiat.

Great piece. Bell's work was so amazing, and still so underappreciated!