Sing To Me Of Free Jazz Gurus & Outlaw Bikers

Pharoah Sanders and Sonny Barger leave very different legacies

Pharoah Sanders

Pharoah Sanders, 2015 (Photo by Tim Charles)

Pharoah Sanders was the heir apparent of John Coltrane's move, sparked by spiritual concerns, toward playing free jazz with an emphasis on the outer edges of the tenor saxophone's voice, with a great deal of attendant overblowing and use of harmonics. But he also possessed a warm, deep tenor tone that made the link with jazz music's past.

The black free jazz community in the second half of the sixties and going into the seventies, was heavily immersed in both Pan African spirituality and a search for the roots of Black classical music. Both of these influences had a strong spiritual element, which made them natural heirs to Coltrane's deeply spiritual recordings, A Love Supreme and Ascension. The very idea of free jazz in the manner heard on Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz or Don Cherry's Where Is Brooklyn? or Coltrane's Ascension, grows from classic New Orleans jazz, based on group improvisation around chordal structure and the building of contrapuntal lines. In free jazz, there is no real chordal structure, but there certainly is counterpoint.

The squawks and squonks that are played on a variety of instruments, but which seem particularly well suited to the saxophone, convey a vocal quality, a chanting or wailing or grieving or bellowing. Sanders and Archie Shepp were contemporaries who carried the torch for free jazz tenor players, and both were perfectly capable of blistering the walls with their sonic intensity, an intensity that Coltrane worked hard to match on Ascension. It's interesting to see Sanders and Shepp's development in the years following Coltrane's death. Both continued to play free jazz and emphasize Black American political and spiritual experience in their music, but Sanders moved into the direction of soul while Shepp went a bit funkier with tracks like "Attica Blues."

Sanders joined Coltrane's quartet and played on several sessions besides Ascension, including the dual-tenor salvo of Meditations and the posthumous releases Stellar Regions and Om. By this time Coltrane's group included his wife Alice on piano, and Sanders continued to work extensively with Alice Coltrane after John's death, playing on such classic records as A Monastic Trio, Ptah the El Daoud, and Journey in Satchidananda. But Sanders' playing on these recordings as well as his own Impulse records, released and recorded during roughly the same years, is markedly different than the direction he and John Coltrane were pursuing together. It's not subdued, but there is a wider range of both volume and overall saturation of sound. He seems to return often to A Love Supreme as the template, but his musical direction is clearly his own.

Sanders' first Impulse session as a leader, Tauhid, was recorded in 1966, the same year that Ascension was released. But Sanders' approach here could not be more different. Sanders often lays in wait through the development of a piece by a rhythm section that includes Henry Grimes, Nat Bettis, Roger Blank, Dave Burrell, and Sonny Sharrock before entering, not on his trademark tenor, but on flute instead. The album leadoff track,"Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt" is a stunning landscape that flows from section to section, offering a different vision of how free jazz could be played.

On his next record, Karma, Sanders started long musical relationships with Lonnie Smith and vocalist Leon Thomas, and the results are amazing. While the pieces he records for his next few records are generally long and meditative, he uses ostinato figures, not just in the bass and keyboard, but also the front line instruments to create a mantra of sorts that helps focus the listener's attention so that she can more readily absorb the soloists' playing. Sometimes this mantra takes the form of a chant as on the first track, "The Creator Has a Master Plan" with Thomas intoning the words following a long instrumental opening. Pharoah gets to some free style blowing much later in the piece, but these sections are much easier for listeners to assimilate, tempered as they are by the completely different vibe that surrounds them.

In 1970 Sanders hit a new stride with Thembi, a record of shorter tracks recorded with two different groups of musicians and on which he played a variety of woodwind instruments, many of African origin. The record is bright and offers the listener both energy and meditative aspects. For example, the opening track, Lonnie Liston Smith's "Astral Traveling," creates a shimmering surface from Liston's Fender Rhodes playing with suitcase vibrato and sustain pedal effects driven by some handheld percussion and topped with Sanders' gentle soprano sax. It's followed by one of the album's most full-throated free jazz scream rants, "Red, Black & Green." Of course, it's a revolutionary number, the colors referring to those of the Pan African flag designed by Marcus Garvey.

Thembi really puts the lie to the idea that Pharoah Sanders was just a free jazz player, and the more that you listen the man's entire output, the more you realize that he was that rare natural musician who simply pulled what he was playing out of the wind. Sometimes that music was loud, intense, and chaotic, but just as often it was not. Subsequent Impulse albums found him exploring island and African musics ("High Life" from Wisdom In Music) as well as Indian and other South Asian music ("Wisdom In Music").

After the Impulse years Sanders had a tough time with record labels through the eighties. But in 1996 Sanders worked with producer Bill Laswell on Message From Home, a record that demonstrated the artist's commitment to his message while placing him in a modern musical environment. With the exception of Laswell's beats and some effects the music is, interestingly, not that exotic to the ears of long time Sanders listeners--when the seventies ended he was already focusing on rhythm and bringing influences and sounds from all over the world. But Message From Home is, in a lot of ways, Pharoah Sanders' Tutu, and it helped revive his career for many listeners.

Some of the stars of the London jazz scene that has flourished since 2017 or so--Shabaka Hutchings, Maisha--owe a clear debt to Sanders. He spent most of the 2000s recording and playing with other groups of musicians who acknowledged his influence on them, including David Murray's Gwo-Ka Masters and Kahil El'Zabar's Ritual Trio. Regardless of the musical setting, Sanders' playing always sounds vital, fresh, and timeless.

Listening again to Floating Points/Pharoah Sanders on Promises, effectively Sanders' last recording. Marveling at how, at 80 years of age, he was able to pull this music from inside of himself and still play within the framework that Sam Shepherd provides. That's the key, really, to Sanders' success at keeping his career not only afloat but always moving into new territory: he truly is just playing his inner voice, expressing himself deeply through the horn, which is the goal of any great musician. He remained committed to passing his knowledge and experience on to new generations and he remained a spiritual seeker, working the alchemy of music to turn human experience into divine expression—finding the divine in the human.

That the music of Pharoah Sanders still has the power to invoke this spirit of awe and wonder in me speaks volumes, not only about the kind of musician Pharoah Sanders was, but about the type of man that he was.

Sonny Barger

Sonny Barger died on June 29, 2022, but for whatever reason his public funeral was not held until this past weekend in September. Barger's hometown of Stockton, California, did not really want the influx of outlaw bikers and other malcontents to invade the Stockton 99 Speedway, but as usual with the Angels, they didn't really get a choice.

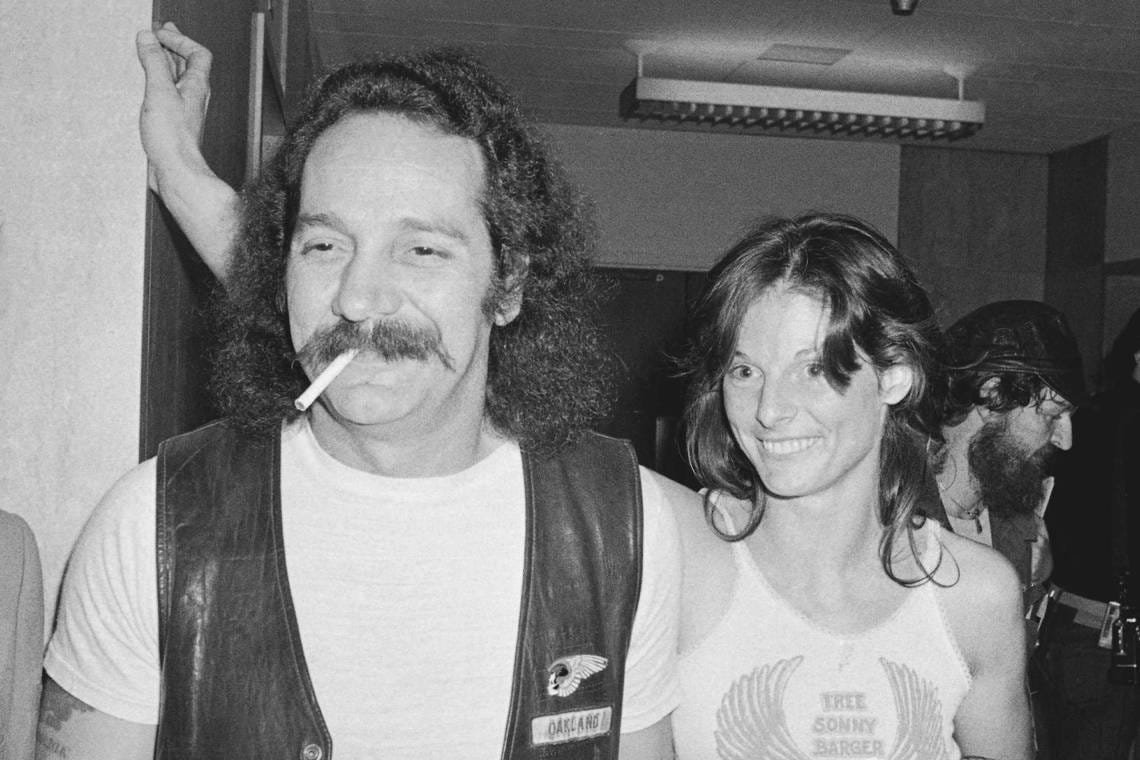

Sonny Barger & wife Sharon, 1980 (Robert H Houston | AP Photo/Robert Houston, File)

Sonny Barger was one of the founders of the Oakland chapter of the Hell's Angels motorcycle club. His crew had the iconic skull with wings insignia of a deceased biker Barger had ridden with in an earlier club made into patches, which they wore and which became the emblem of the Angels. The Oakland chapter was not the only Hell's Angels club in California, and Barger was instrumental in bringing the various chapters from around the state together into what would become a national organization. Like a mafia don, Barger convinced these other groups that they would have more influence and safety if they banded together. He was well liked within the group, and in a short time the group's headquarters was moved to Oakland, with Barger as de facto leader.

Make no mistake, the Hell's Angels were and still are a major criminal enterprise, having engaged at various times in drug trafficking, prostitution, selling and threatening to use explosives to blow up various targets, gun running, and other nefarious pursuits. And Barger was perhaps among the worst. Predictably, he went to prison on stints for drug trafficking and plotting to murder rival motorcycle gang members, but there was more to him than his official rap sheet. At a 1973 trial, Barger testified on the witness stand that he had arranged to swap guns and explosives, or information on their locations, for the release of jailed Hell's Angels. Barger sold it as a way for the cops to get the drop on radical and subversive groups like the Weathermen and the Black Panthers, and apparently they saw it that way as well.

One of the seeming oddities in Barger's Stockton funeral memorial was the appearance of far right propagandist Tucker Carlson, who reportedly cleared his calendar in order to fly to California to participate in the festivities. At first glance it may appear odd that Barger and Carlson should have much in common, but take a closer look and the pieces fall into place.

Like the MAGA crazies that Tucker panders to, Sonny Barger didn't see himself or the Angels as criminals, but as outlaws who struggled against a system that favored the corrupt and the weak. He saw himself as a defender of white culture and though he denied that the Angels are a whites only club, there are and have never been many non-white members. Of course, Barger didn't trust the government, had little regard or respect for law enforcement, and operated by a credo that is essentially that of the bully: the strong doing what they can and the weak suffering what they must. And he wrapped it all in a shroud of patriotism, a proud American who hated hippies, communists, and activists.

How did the Angels manage to become part of the sixties counterculture given their authoritarian and criminal tendencies? Barger had a lot to do with that. For one thing, he knew his audience and membership and was acutely aware of the judgement imposed by straights on biker culture. He was adamant that the Angels be referred to as a club, not a motorcycle gang. He never missed an opportunity to sell the Angels as a group of guys with long hair who simply loved to drive around the country on their Harley Davidson bikes.

Second, he had some significant help along the way. A young freelance writer named Hunter S Thompson wrote a piece on the Angels for The Nation and subsequently was offered a book deal to write a full length account of the scourge of the highways. Thompson spent a year embedded with the Angels, earning their trust when it became apparent that he wasn't too interested in living a status quo American lifestyle either. But Hunter got pulled too far into the orbit of the club and its leader. You can hear the development of his gonzo style of journalism as the young writer is drawn into the group's odd mystique, even as he realizes that they are engaging in some fairly serious criminal behavior.

Thompson's fascination with Hell's Angels was broken when he was punched and stomped by a group of them for suggesting that one of the group stop beating up his wife. The book ends with him driving back to San Francisco and never looking back:

“It had been a bad trip ... fast and wild in some moments, slow and dirty in others, but on balance it looked like a bummer. On my way back to San Francisco, I tried to compose a fitting epitaph. I wanted something original, but there was no escaping the echo of Mistah Kurtz' final words from the heart of darkness: "The horror! The horror! ... Exterminate all the brutes!”

Sonny Barger’s call-in to a local radio station post-Altamont (from Gimme Shelter)

Hell's Angels put Hunter S Thompson on the map, but it also increased the mystique and cache of the Hell's Angels and of Sonny Barger. Another element giving the Angels a patina of counterculture respectability was the friendship between The Angels and San Francisco's biggest counterculture stars, The Grateful Dead. The Dead and the Angels had a relationship that went back to their first days at Haight Ashbury, and Gerry Garcia never renounced that relationship, even after the Angels were implicated in the melee and murder that took place at the Altamont Speedway where the Rolling Stones played a free concert. In typical fashion, Barger blamed that fiasco on Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones and it's clear that The Stones rubbed him the wrong way from the start.

It was ironic, then, to see Barger's memorial service being held at the Stockton 99 Speedway in San Joaquin, just 38 minutes southwest of the Altamont Speedway and its ghosts presiding over the dusty, desolate landscape. There was a lot of apprehension in the air on the part of residents and law enforcement in the area. The Sacramento Bee's announcement:

Services at Stockton 99 Speedway, 4105 N. Wilson Way, begins at 2 p.m. Saturday. The tightly controlled, invitation-only five-hour ceremony will feature speakers, music and remembrances of Barger. Motorcycle clubs’ representation at the service will be limited. Weapons and drugs are prohibited.

In the end, around 7000 people showed up to pay their respects, according to the Stockton Record, and there were no significant events reported. In his remarks, Tucker Carlson quoted Barger's final statement, released after his death: “‘Stay loyal, remain free, and always value honor.’ And I thought to myself, if there is a phrase that sums up more perfectly what I want to be, what I aspire to be and the kind of man that I respect, I can’t think of a phrase that sums it up more perfectly than that.”

I wish Hunter S. Thompson had been there to comment on that.

Exterminate all the brutes.