In the spring of 1980, I was about to graduate from high school. A small group of friends decided we would spend the senior tradition of ditch day hanging out together at the beach. We'd see how things were there for a while, and then we'd head somewhere else if we wanted.

We drove up the north shore of Lake Michigan and found a small beach somewhere between Wilmette and Lake Forest where we sat around, talking about the important things we were going to do with our lives. We brought candy and snacks as I recall. Someone brought a little pot, which I remember getting buried in the sand in a fit of paranoia.

It was kind of a cold day, and by early afternoon we had had enough of the beach. We decided to clamor into the car and drive to a nearby shopping mall with a huge food court. And so we arrived, looking fairly bedraggled and probably not like kids who had planned to visit the mall that afternoon.

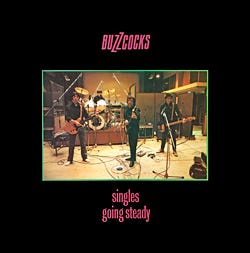

There was a record store there, one of those mall chains, and there was no question that I was going to take the opportunity to browse the bins because I was constantly looking for records I had read about but not yet been able to find at my local record shop. Browsing through a rack near the front of the store---maybe a sale rack, don't remember--there was a brand new copy of Singles Going Steady by the Buzzcocks. Released by IRS Records in 1979, the compilation was the first record by the band released in the U.S. as an introduction to the band for American listeners.

I had recently read about the band and this record, which compiles their eight U.K. United Artists singles presented in chronological order on Side One, with the B-side of each single, also in chronological order, on Side Two. I couldn't believe my good luck. I bought the record. Don't remember the food court much at all, except that one of my friends got his foot caught in a wrought iron chair like the ones in some Parisian cafe, and he fell and knocked the chair over. We might have been asked to leave the food court.

When I arrived home I immediately sequestered myself in my bedroom and broke the plastic on my copy of SGS. I played the record. Side One. Side Two. Side One again. And again. Side Two.

These guys, I told myself, are the new Beatles. They were writing great songs with memorable melodies, and they were pushing hard at the boundaries of the classic pop form. They were complete masters of what they were doing. Like a number of excellent punk-influenced bands before and since they combined the whipsaw energy and distortion of punk with an undeniable pop sensibility. But not with an undue emphasis on the pop side. These guys were much more Nirvana than Blink 182. If I had to hazard a guess I'd say that Billy Joe Armstrong is a Buzzcocks fan--which he is.

They seemed like a secret that, once discovered, would shoot to the top of the charts. How, I wondered, could a group have released so many fantastic records, and yet my world was full of people WHO DID NOT KNOW? I mean, even the B sides were unbelievably fantastic. When I heard "Everybody's Happy Nowadays" the top of my head completely blew off. And then Steve Diggle's vocal on "Harmony In My Head" brought it back. There was no doubt I would see them at the first available opportunity.

I got the chance to see the Buzzcocks in November of 1980 when they came to play in the U.S. Northeast for a week. The group arrived at Logan Airport on November 1980 and proceeded to do a combination of interviews and live appearances for the next seven days. They played shows at My Father's Place in Long Island, The Rusty Nail in Amherst, Brown University in Rhode Island, and the Ritz in NYC, where they also managed to take in David Bowie in The Elephant Man. On November 25, they played The Bradford Hotel Ballroom in Boston. I was a student at Berklee College of Music at the time, and I saw a few concerts at the Bradford, but the main ones I remember were Jonathan Richman and the Buzzcocks.

The Bradford, located at 275 Tremont Ave., had once been a luxury hotel boasting 350 rooms, all with their own bath and air conditioning. There was a fantastic restaurant on the top floor and roof of the building, and the ballroom saw dancing and live shows by the likes of Duke Ellington. That seems to have started to decline when Boston defined The Combat Zone, as it was colloquially known, in 1974. The Zone was meant to contain adult entertainment to a specific area of the city, out of the neighborhoods where families lived. It was the first attempt to do so in the United States.

The Bradford was no longer the hotel it had been in the 1920s or in 1931 when radio station WBZ moved its studio to the hotel. By the time I was going there, a bunch of photographers was renting the old top floor restaurant space as a studio base from which they took photos documenting the beginning of the end years of the Combat Zone. By this time the area was more seedy than truly dangerous, although there were higher rates of crime in the area immediately around the Zone and the Boston Commons.

Concerts were held regularly at the Ballroom, and most of these were punk and post-punk bands--what we'd now call alt-rock, I suppose--and the night of the Buzzcocks show saw Boston punks turned out in all their finery. It being an all-ages show, there were girls there with spiked blond hair and safety pins through their ears who couldn't have been more than fifteen. Guys of a similar age group, as well as older ones who worked in a record store or maybe a club and were most likely to self-identify as someone who was in a band. There were students as well--most from Boston University. I was, let's say, one of the few Berklee students who was likely to be at such a show. It's much more a music business school nowadays, but back then it was mostly hardcore jazz cats and technique-obsessed fusion players.

I remember being in the bathroom washing my hands and looking in the mirror at the parade of kids and rock nerds mixing it up. A small coterie of Mod guys was preening in front of a couple of mirrors. A couple of elderly gentlemen moved towards the sinks. They appeared surprised but not really alarmed by the influx of preening teen peacocks.

"What's the deal?" one asked of the Mod boys furiously combing and adjusting their finery.

"It's the Buzzcocks!" exclaimed one, eyes wide in the realization that there might be someone out there WHO DID NOT KNOW.

"Oh, I see," said the elderly guy, who proceeded to wash his hands and continue slowly on his way back to the bar, or the hotel.

It was a moment that always stuck in my head for some reason. The juxtaposition: the old and the new, the inevitable decay of the magnificent, the way that even the area designated by the city fathers to be the seedy area of town was falling to ruin. Not the ruin of adult business, but the ruin of things running down, running into the ground, slowly ending. The deco grandeur of the Bradford had faded, and now the urban decay that had replaced it was fading.

The Buzzcocks put on a terrific show. I remember being enthralled by Steve Shelley and energized by Steve Diggle, guitarist and second vocalist. They played "Harmony In My Head," "Noise Annoys," "Everybody's Happy Nowadays," "Ever Fallen In Love," "Something's Gone Wrong Again," "Times Up," and even "Boredom." They played other songs as well, but these are ones that imprinted themselves on my memory so that I can still remember them clearly.

From what I can tell the Bradford continued to function as it was when I was there until 1987 (Miles Davis played one of his comeback shows there in 1981), at which point it became the Treemont House. These days it's a Courtyards by Marriott, operated as a boutique downtown property. Marriott says they have 'restored the interior to the opulence and glamour of its 1920s design.' For those seeking to book an event at the hotel, there are three historic renovated ballrooms.

I wonder if I could book a band there today. Certainly not the Buzzcocks. Pete Shelley died in December 2018, and that's that. The band did continue to release great records until then and had live gigs booked when Shelley passed away.

Bonus Tracks

BMG has just announced that they are reviewing historical contracts, and will look to address the 'music industry's shameful treatment of black artists.' If they follow through on this, it is a big deal.

Country Music Is Nothing Without Black Artists In this excellent piece, writer Andrea Williams talks to Rissi Palmer and Mickey Guyton about the influence of Linda Martell's 'Color Me Country' fifty years on.

Listen to Mickey Guyton's new single, "Black Like Me."

HMV Owner Doug Putnam talks about the reopening of the British music chain stores.

Sonny Rollins on the Pandemic, Protests, and Music Rollins talks to The New Yorker's Daniel King about what's going on, turning ninety, and Lester Young.

Closed: Record Mart, Manhattan's oldest record store, located in the Times Square subway station.

The Discogs listings reveal the most wanted and most expensive Brian Eno albums listed on the service.

Bitches Brew: How Jazz Became Studio Music, my new article at NDIM, looks at the genesis of the seminal Miles Davis album and how it changed the way jazz was recorded and produced.

Music Aficionado blog has this piece on the story behind Pat Metheny album 80/81.

Terry Quirk, best known for his cover art on the Zombies album Odessey & Oracle, died last month. Quirk's misspelling was kept as part of the title to what has become a classic rock album.

What Did Bach Sound Like To Bach? A fascinating read about how space and the way that it dampens or amplifies various sounds influences composers.

5 Tracks I'm listening to this week

Leaving you today with the official video for Yola's single "Ride Out In the Country," a great song that will have you humming it after just a couple of listens. The song is from her 2019 album Walk Through Fire, one of the best genre-defying albums since Roberta Flack. Is it country? Is it soul? Is it pop? Who cares--it's Yola.

As always, thanks for subscribing and reading. Some cool changes coming to the newsletter soon. In the meantime, have a pleasant week.