The Cover Art of Robert Springett

His work for Herbie Hancock in the seventies articulated an Afrofuturistic vision

Beginning in 1972, Herbie Hancock teamed up with artist Robert Springett to produce a series of albums with a vision rooted in Afrofuturism. Although the term would not be officially coined until 1993, it’s pretty clear that a number of musicians, including Sun Ra, Hancock, Lee “Scratch ” Perry, Afrika Bambaataa and George Clinton were onto the vibe much earlier.

Hancock has always been a jazz musician with one eye on the future. He helped popularize the sound of the electric piano, then moved on to synthesizers and electronic sounds and beyond to funk, hip-hop, jazztronica and more.

In the 1960s Herbie Hancock was a dominating force on the jazz scene. He was a member of Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet, and he cut a series of Blue Note albums as a leader that demonstrated both his writing and his playing. As the decade ended, change was on the horizon. Davis moved on to experimenting with different recording techniques, electric instruments, and a variety of musicians, including Hancock, who floated in and out of the studio.

As for Hancock, he formed a sextet; far from a commercially viable option. He also became more interested in electronics. But what’s far more interesting is the total music and presentation he put together for the band’s three albums. Musically he combined elements of free jazz with the groove and atmosphere he helped Miles explore on In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. He underlined the rhythm at times with supplemental percussion, giving a tribal or Latin foundation beneath the electronic sounds he was experimenting with.

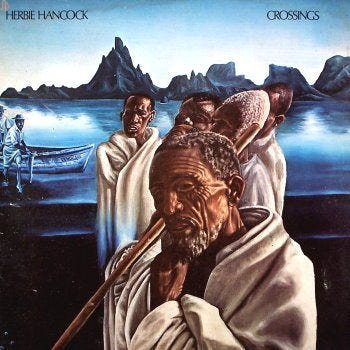

Crossings, released in 1972, was Hancock’s second with the so-called Mwandishi band, named after their first album. That album had a plainer, more ‘jazz record’ design that really gave little clue as to the music that was on the vinyl. Crossings moved further forward with its Afrofuturism. Sonically it moved the synthesizer work of Hancock and Patrick Gleeson farther forward.

Visually, artist Robert Springett creates a setting that is at once familiar and yet conveys a distinctly alien feeling. Rendered in shades of blue, a group of elderly men wearing plain white robes stand together on the shore of a lake while two men with a vaguely South American garb are bringing a small boat onto the shore. Who are they? Have they just arrived or are they here to meet the men with the boat?

“There are Africans that are pulling a boat up on a beach-that kind of primitive element, although the music itself is very modern and avant-garde. There’s a rawness, too, that is kind of a tie-in with the primitive and the kind of exploratory nature of stepping into areas of the unknown. The [cover and music] relate to each other in that sense.”

–Herbie Hancock, talking about the Crossings album cover.

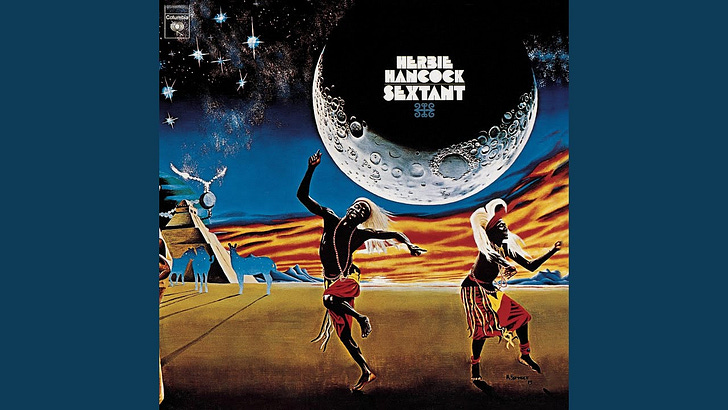

Sextant was Hancock’s last album with the Mwandishi band and he moved to Columbia Records. For this album Springett offered a truly dazzling, kinetic piece of artwork on the front cover. Two dancers in unmistakable but colorful tribal garb occupy the foreground. In the background are a couple of blue horse/zebra critters and a Mayan-style pyramid all watched over by a starry night sky and an enormous crescent moon.

The back cover contains the album credits and an illustration that looks like one of the elders from the Crossings cover, wearing a brown robe this time. Towering behind the elder is a large Buddha head, and the road is adorned with lotus flowers and a string of mala beads. It fits because around this time Hancock began to practice Nichiren Buddhism. The Buddha theme would return two albums later, on Man Child, with cover art by Dario Campanile.

The music on Sextant is pretty similar to that on Crossings and Mwandishi. “Hornets,” the sole track on Side Two, shares a great deal of energy with some of Miles Davis’ electric versions of “Directions.” Side One features “Hidden Shadows” a slow groove safari that makes ample use of Bennie Maupin’s deft bass clarinet work.

But it’s the opener, “Rain Dance” that steals the show. A whirling intermix of electronic and rhythmic sounds, it is surely the music that the dancers on the cover are moving to. This was as far as Hancock and company pushed this particular envelope, yet this track predicts a lot of electronic music to come and still doesn’t sound dated.

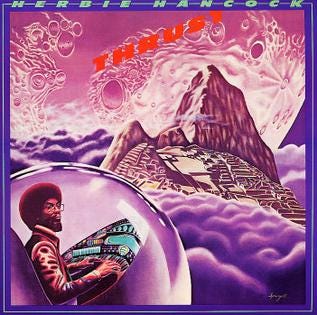

Springett didn’t provide the cover for Hancock’s next album, Headhunters,but he did the followup, Thrust. Thrust continues Headhunters’ focus on the groove, with the opening and closing tracks giving straight ahead funk realness. “Actual Proof” is the jazziest number, but the killer here is the eleven minute make out track “Butterfly” which uses Maupin’s dusky bass clarinet in one of his most beautiful performances on record.

Springett’s artwork is a little bit less detailed and magical here. It features Hancock himself enclosed in a spaceship with a bank of keyboards for controls, descending through a purple atmosphere towards what looks a lot like Machu Picchu. But of course the music itself had changed as well, with more emphasis on the funk and dance elements of the music. It was less complex and somewhat more commercial. Regardless, Hancock has continued to use Afrofuturism as a touchstone for his tech music’s visual presentation.

Springett produced a couple of other album covers in the mid-1970s. He did the Vietnamese countryside influenced Hard Nose The Highway for Van Morrison, and in 1975 he did the cover art for Graham Central Station’s Ain’t No Doubt About It. But it’s his work with Hancock that created a vibe and look that is so readily identifiable as Afrofuturism long before the phrase came into use.

New Directions in Music is written by a single real person. It is not generated by AI. Please help spread good content by reading (Thank you!) and sharing this post with a music loving friend. If you like what you see, please sign up for a free subscription so you don’t miss a thing, or sign up for a paid subscription if you can.

Being a record store jockey for a handful of years (1977-1982...I was 22 in '77), we always saw those jackets, of course, and wondered about them. Over time, similarly-styled artwork kept appearing (on more than just Hancock albums) on albums by Osibisa (if memory serves), and you mentioned a couple others.

If you "do requests," Marshall, I'd love to know more about Moshe Brakha, who, among many other album jackets, photographed and designed the album cover of Boz Scaggs' "Silk Degrees." He had such a distinctive and stark look, but his photos on jackets seemed to define a brief era of jacket design! Thanks for this....a 50-year mystery for me, solved!

Springett made pictures that very much complement Hancock's music on those albums.