The Slow Process of Protest & Resistance

Hello, everybody. Obviously a lot has happened since last week. In light of the murder of George Floyd and the nationwide protests that are bringing attention to the issues of police brutality, I considered not publishing a newsletter, but that didn’t seem right. Nor did I feel like running the piece originally slated for this week.

Instead, I am running a piece that I wrote back in 2002 inspired by the conviction of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bomber Bobby Frank Cherry and the opening of an exhibit called ‘Without Sanctuary’ about the history of public lynching in America. It talks about the sometimes glacial speed of social progress and the way that African American jazz musicians have always been a part of the process of protest and resistance. My hope is that it will provide readers with historic context and perhaps inspiration for the struggle that still lies ahead.

The Slow Process of Protest and Resistance

The recent conviction of Ku Klux Klansman Bobby Frank Cherry no doubt made some folks feel good about the strides the United States has made in racial equality and relations. Likewise the recent opening of "Without Sanctuary", an exhibit of photographs and artifacts that document and bear witness to the thousands of African-Americans who lost their lives to lynch mobs in the twentieth century. We can take comfort in the fact that these things don't happen today, right? Tell that to the family of James Byrd, Jr., who in 1998 was stripped, chained to a pickup truck, and dragged until he was decapitated.

Sadly, there will always be ignorant people capable of performing heinous acts against their fellow humans. That is unfortunate. What is unconscionable, however, is that the actions like those of Cherry and the lynch mobs that were made up of folks just like him went unpunished for so long when the evidence was right there in front of us. Why did it take so long for the abomination of lynching to be confronted? Why only now, 63 years after Billie Holiday's recording of the anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit" was released, are the grotesque images referred to in the song, often sold as postcards and mementos, on display for the average American to see?

"Strange Fruit" has always held a unique place in the American songbook and in the work of Billie Holiday. There have been many accounts of how Holiday came to perform this stark and moving piece of music. In his book Billie's Blues biographer John Chilton mentions that Holiday wanted the title of her autobiography to be comprised of "Strange Fruit's" last two words, Bitter Crop, but her publisher did not find it a suitable or marketable title. This clearly shows Holiday's recognition of the importance of the song.

Holiday never saw a lynching first-hand, despite some fictional liberties to the contrary in Lady Sings the Blues. What makes "Strange Fruit" such a powerful song and creates its ability to cast a spell over an audience is the fact that it makes such first-hand witness unnecessary. The song itself bears witness with its sense-rich poetry—"Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh/Then the sudden smell of burning flesh." And it says something much more deep and profound than that lynching itself is wrong. It intimately whispers to the listener "this is a scene made possible by racism in America. It is the extreme case, but it is the logical conclusion of the many smaller racist acts committed daily by one group of people against another."

It is this subtext that gives the song power even now when many Americans tell themselves that racial inequality and racism are things of the past, even though they know there is evidence to the contrary. Indeed, it provides a call to arms against racism against any group and discrimination in any form. The people who attended lynchings in the South were often no different than most folks in their community. Many of them did not think of themselves as racist and they were often held in high regard in their communities. They left lynchings, often having purchased postcards of the events as souvenirs, and went back home to their children, their jobs, their churches, the social fabric of daily life without much, if any, sense of conflict.

How can that be? One answer is that racism was so entrenched in American society that it was possible for people to participate in or observe these heinous acts and go about their lives as if nothing had occurred. More than one observer of the "Without Sanctuary" exhibit has commented that the most haunting images to be found there are not those of the victims of lynching, disturbing as they may be, but rather the observers who smile back at the camera as though they were at a church picnic.

In her essay "Strange Fruit", Dr. Angela Davis makes a convincing case for the argument that "Strange Fruit" played a catalytic role in "rejuvenating the tradition of protest and resistance in African-American and American traditions of popular music and culture." This is absolutely true. The very creation of jazz and blues music in America was a process of protest and resistance, and much of the subsequent history of these musical genres has been about reclaiming that process from the hands of those who would subvert their meaning.

Soon after black musicians in New Orleans and across the American South, Southwest, and Midwest began to play a style of music that would come to be known as jazz, white bands were cropping up in New York City and were recorded before any of the black bands. We have no record of some of these early musicians because of the lack of interest in recording them. Subsequently, black musicians began to perform jazz in a different style. Don Redman began writing more elaborate arrangements for Fletcher Henderson's band, and a young composer named Duke Ellington began a quest to create a new kind of black American music, one that was woven from the threads of black life in this country and reflected the experiences and emotions of the average black person.

It is a mistake to believe that simply because Ellington didn't write explicitly angry music or express outrage at racial injustice in most interviews that his music lacks the dimensions of "protest and resistance." The very existence of such compositions as "Harlem Airshaft" and "Black and Tan Fantasy" belies such an interpretation of Ellington or his music. It was Ellington who suggested that jazz be recast as "Negro music" to avoid any confusion over its meaning and origin.

In the 1950s and 60s the public spectacle of lynching had not completely disappeared, but the number of such events had decreased to the extent that they were a rarity. That doesn't mean that the killing stopped; how could it when the underlying racism that allowed lynching in the first place had not been rooted out? In the face of the mounting civil rights movement and other demands for racial equality the format simply changed, and many killings took place in the dark depths of night on back roads far from the view of the American public. But there was usually not much doubt who was responsible. In most Southern towns it was generally known who the most active Klan members were, and even if it were not known, the inability of these killers to keep from boasting of their actions made them well known.

Within a few weeks of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, FBI field agents had identified several suspects in the case, but the prosecution of these offenders was blocked by J. Edgar Hoover, who at the time was having field agents pass information to known Klansmen regarding the whereabouts and activities of civil rights workers, thus facilitating the Klan's reign of terror. This wasn't merely a governmental agency averting its eyes in the face of racial violence; it was actively encouraging such activity.

When the federal government did turn a blind eye to racial injustice and violence, jazz musicians were among the African-American leaders who spoke up. The 1957 Little Rock school integration incident had polarized the United States on the subject of race. The Supreme Court had decreed that nine black students were to be allowed to attend Central High School in Little Rock. On September 2, 1957, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus called in the National Guard, ostensibly because he had heard that white supremacists were going to descend on the town. He declared that Central was off-limits to black students, and the town’s black high school was off-limits to whites. More disturbing still was his statement that “blood would run in the streets” if the black students attempted to attend Central.

Louis Armstrong told a reporter that President Eisenhower was a hypocrite and that he (Armstrong) was sick to be a goodwill ambassador for a country that was silently condoning racist activity. There was a great deal of controversy, but Louis stood by his statement. He also didn’t make the trip to the Soviet Union that had been planned for him by the U.S. State Department; Armstrong’s statements to the press stood out as a defining moment in his life and career.

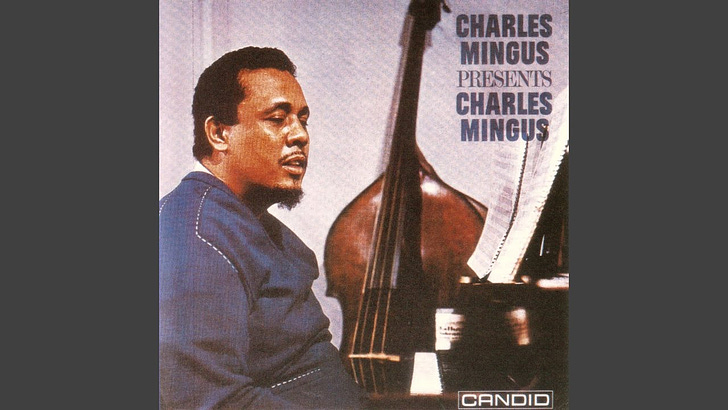

Charles Mingus, one of the new breed of jazz musicians who suffered mightily in his career because he refused to bow to predominantly white audiences, record labels, and club owners, commemorated the Little Rock event in his composition “Fables of Faubus.” In it he called Faubus "sick" and "a fool." Mingus came from a new generation of jazz musicians, those who had pioneered bebop as a way of reclaiming jazz from the commercialism of predominantly white swing bands. Again, even when artists like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Mingus didn't make outright political statements, they were implicit in the music itself as well as the styles and attitudes of the musicians.

By the end of the 1960s, many of the best jazz musicians had fled the country for Europe where they were not only treated with respect as musicians but where they could live largely unfettered by the racist mentality that still plagued America. The avant-garde jazz movement became a focal point for the anger and frustrations of many younger musicians, with some, like Archie Shepp, playing music that was often confrontational and difficult for many to listen to or understand. The AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) was formed in order to provide musicians and composers with the ability to get their music heard as well as the tools (like ownership of their own work) to make a living. Some of the younger musicians saw fit to criticize musicians like Ellington and Armstrong for not being more outspoken. What they failed to realize was that they themselves were merely the latest in a long line of individuals who facilitated the process of protest and resistance that had defined American jazz and blues music from the outset.

Bit by bit these individuals were able to change the social and cultural landscape of our country to the point where the conviction of Bobby Frank Cherry and his ilk and the "Without Sanctuary" exhibit became possible. They did it by speaking to individuals, not to the government, and not to the American institutions that made lynchings and bombings possible in the first place. Yet there are those who suggest that none of this should happen. Some will say that the lynching exhibition and the Birmingham bombing trial merely create more divisiveness and reopen old wounds. They forget that for some, those wounds were never closed.

Bonus Track

Natalie Weiner, who describes herself as ‘just another Brooklyn writer’ penned this marvelous remembrance of Jimmy Cobb for NPR. Cobb, the last surviving member of the Kind of Blue sessions, died at the age of 91.

Leaving you today with Stevie Wonder’s ‘Living For The City.’ This is the complete album cut from his 1973 album ‘Innervisions.’ Same crap, different decade.

Wishing everyone a good week and a safe week. Keep the faith, and please forward this newsletter to someone who needs to read it. Thanks.