**Quick note: If you enjoy or find value in this article, please give it a like by clicking the heart icon below the title/subtitle or at the end of the article. Your vote is much appreciated**

Inspired by insomnia and the myriad stories about the fiftieth anniversary of the Woodstock Festival I watched a marathon of 'Music of' various decades recently on CNN. I came into the cycle at the start of the 1970s, then saw episodes on the '90s and '2000s (not sure what happened to the '80s, but don't care). Then they repeated the 1960s episode I'd missed and then there was a second hour on the 1960s that covered more than just the decade's music.

Near the end of this last piece was Jack Kerouac's 1969 appearance on William F Buckley's show. This conversation, taped only a few months before Kerouac's death, finds him repudiating any credit for creating the hippie movement and demonstrates that the writer was not sympathetic to the tenets of the burgeoning counterculture movement.

Kerouac didn't consider himself a counterculture figure nor a hero to be emulated. He considered himself a writer first and foremost. He generally considered the beatniks to be somewhat of a nuisance, but generally tolerable. But he never wanted to be a hero. He didn't believe that his books, even the classic On the Road, were tales to be emulated, but rather as documents pulled from the fire of a life that was often less than exemplary.

He was a law and order guy, an all-American raised in the era when guys drank and played football (he received a football scholarship to Columbia, later dropping out), and he was supportive of the Vietnam War. In many ways he was a member of Nixon's 'silent majority'. He identified heavily as a Catholic despite the Beats' experimentation with Buddhism. A working class guy who happened to be a writer.

Jack Kerouac never intended, and was ill-prepared to be, any kind of influence or example, and when he was confronted with it he felt compelled to mock it, as in this passage from Big Sur:

"I’m supposed to be the King of the Beatniks according to the newspapers, so but at the same time I’m sick and tired of all the endless enthusiasms of new young kids trying to know me and pour out all their lives into me so that I’ll jump up and down and say yes yes that’s right..."

It seems probable that the thing that Kerouac couldn't stand about the hippies, what distinguished them from the beatniks, was their politicization. He came from a working class background, a shot and a beer, and in the Buckley clip he is exactly like the drunk uncle or the drunk war veteran at the end of the bar who blames everything on lawless rebellion, on the way long hair and blue jeans show a lack of respect and how these kids have no sense of patriotism and won't stand up to the communists.

And the humor. Humor is not a major element in Kerouac's books, and if he disagreed with you strongly enough he seems more like the kind of guy who would throw a punch than a joke. In the various Woodstock pieces that have aired recently I noted a few times the comment from Wavy Gravy (Hugh Romney--he didn't become known as Wavy Gravy until a few weeks after Woodstock) that the security force he headed was a "Please Force" rather than a police force, and that they intended to keep the peace with "cream pies and seltzer bottles."

A lot of hippie political protest was done as street theater or as a put on, a joke. That didn't make it any less effective: when Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies announced plans to levitate the Pentagon or to spike the water supply with LSD, the response was not laughter. But the joke was still on the establishment.

The young people who formed the core of the hippie rebellion that Kerouac so hated were mostly intelligent, literate, educated and altruistic. Unlike the beatniks who formed a counterculture that was ultimately selfish and incapable of radical political action, the hippie movement looked inward in order to better understand themselves and better engage with others, with the ultimate goal of moving society forward. The Woodstock Festival is the shining example of that goal made real because of the combined efforts of an incredible number of people who all wanted it to succeed, not for financial reasons, but because of what it demonstrated to the rest of the country. It's impossible to imagine a beatnik Woodstock.

Max Yasgur, who rented his dairy farm as the site of the Woodstock Festival, was a Republican and a conservative who supported the Vietnam War. He was not happy about the way that some of the young people of the '60s were protesting or the things they were saying about his country. But he was a staunch believer in freedom of speech and a rugged Yankee individualist, and he allowed the festival on his farm much to the chagrin of his friends and neighbors--afterward he was never welcome at the general store. On the final day of the festival he addressed the crowd, telling them:

"I think you people have proven something to the world--not only to the Town of Bethel, or Sullivan County, or New York State; you've proven something to the world. This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place. We have had no idea that there would be this size group, and because of that, you've had quite a few inconveniences as far as water, food, and so forth. Your producers have done a mammoth job to see that you're taken care of... they'd enjoy a vote of thanks. But above that, the important thing that you've proven to the world is that a half a million kids--and I call you kids because I have children that are older than you--a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and I God bless you for it!"

The next wave of counter-cultural literature came from Ken Kesey, a native of Colorado who migrated to California and then Oregon. Kesey was 13 years younger than Kerouac and he went to college on a wrestling scholarship and then on to Stanford's graduate writing program. Like Kerouac, Kesey was a large physical presence who liked to brawl, but Kesey was interested in psychedelic drugs. He volunteered for an Army experiment in which subjects were given mind-altering drugs. He also worked in a hospital psychiatric ward, inspiring his first novel, the brief anti-establishment tale One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

After another novel and a lot more LSD, Kesey took a bus trip across America with his retinue, known as the Merry Pranksters. And who should show up as the driver of Kesey's bus, "Further"? None other than Neal Cassady, the ex-Beat muse and living embodiment of Kerouac's mad angel energy. And Cassady has no problem whatever shedding the crazed holy fool of the night role for the wasted holy fool behind the wheel role.

Kesey was inspired, like everyone else of the time, by On the Road, but Kesey didn’t emulate Kerouac’s lifestyle, his trip was to be free in his own peculiar way. Kesey wanted a big party with a group that was a moving community that could take care of itself and each other, and that was really the antithesis of the loner ethos of the Beats. It was the blueprint for Woodstock.

Neal and Jack and Me. We're together, but we're really alone.

Neal made the swap for the warm embrace of the community, that feeling that maybe the next guy you met wouldn't rob you or steal your stuff or turn you in. Maybe that next person you met would help feed you, provide you with a role in a community where you had value and maybe could come to value yourself. Maybe that next person would lend you their land on which to manifest your dreams, the tribal dreams of a lot of people who weren't really all 'hippies' at all, but who caught the moment and went surfing on it, going ever further.

Kesey embraced his followers. He was happy to gather his tribe around him. He wanted to share his talents. He taught writing. He and his wife raised a family in Oregon and were part of a more traditional community. And Kesey understood the use of humor: “Man, when you lose your laugh you lose your footing.”

Poor Jack Kerouac, he couldn't make that shift, to just living, and it killed him. He was bitter and he wasted the good will his writing had created on remaining aloof and aloft from the Beats and on being outright contemptuous of the hippie generation. Cassady gave Kerouac the narrative voice of On the Road, a voice that Kerouac himself did not possess but which he could put into words, which Cassady could not do. He was able to provide Kesey and his Pranksters a safe and swift journey across the miles, miles that he'd driven many times before, and they were thankful. In return they valued Neal for who he was, warts and all.

Woodstock was one of those events that reinforced America’s sense of community. For a brief time it looked like maybe Nixon was wrong. Maybe the real silent majority were the people who wanted to see their neighbor in the best possible light. The reason anyone cares fifty years later isn’t just because of the music, though that was amazing in itself. It is because for a shining moment it looked like maybe all you really did need was love.

Bonus Tracks

Grateful Dead: ‘Cassidy” The song was inspired by the daughter of a Dead crew member, Cassidy Law, but the lyrics also allude to Neal Cassady. John Perry Barlow, who wrote the song’s lyrics talks about the song, Neal Cassady, the Grateful Dead, and Ken Kesey in this wonderful post at Literary Kicks.

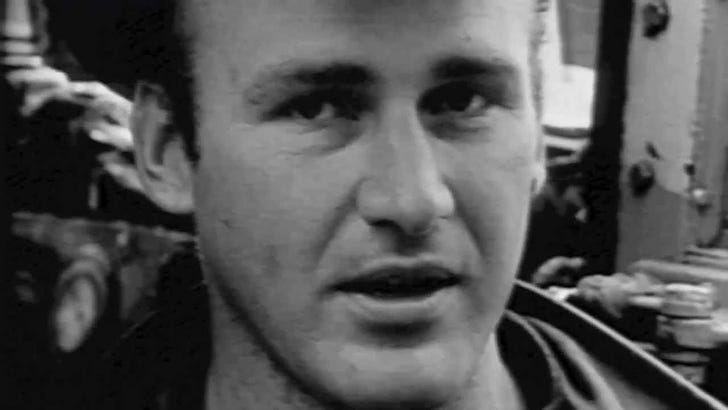

Here’s the younger Kerouac reading from On the Road on the Steve Allen show along with a brief interview about the book. Steve plays some cocktail jazzbo piano behind him. You can only imagine that Jack got sick of this kind of thing pretty quickly.

Thank you to everyone who reads our newsletter, visits the site or checks in on Facebook and Instagram. We also have Spotify playlists.

Now on New Directions at Music”

If you enjoy this newsletter, please forward it to someone else you know who might also like it.

Mind your step as you exit and have a day filled with music.